|

Giraffes in the East African savannas are adapting surprisingly well to the rising temperatures caused by climate change. However, they are threatened by increasingly heavy rainfall, as researchers from the Wild Nature Institute, University of Zurich and Pennsylvania State University show.

Climate change is expected to cause widespread declines in wildlife populations worldwide. Yet, little was previously known about the combined climate and human effects on the survival rates not only of giraffes, but of any large African herbivore species. Now researchers from the University of Zurich and Pennsylvania State University have concluded a decade-long study – the largest to date – of a giraffe population in the Tarangire region of Tanzania. The study area spanned more than a thousand square kilometers, including areas inside and outside protected areas. Contrary to expectations, higher temperatures were found to positively affect adult giraffe survival, while rainier wet seasons negatively impacted adult and calf survival. First exploration into the effects of climate variation on giraffe survival Led by Monica Bond, a postdoctoral research associate in the Department of Evolutionary Biology and Environmental Studies at the University of Zurich and co-founder of Wild Nature Institute, the research team quantified the effects of local anomalies of temperature, rainfall, and vegetation greenness on the probability of survival of the giraffes. They also explored whether climate had a greater effect on giraffes that were also experiencing human impacts at the edges of the protected reserves. “Studying the effects of climate and human pressures on a long-lived and slow-breeding animal like a giraffe requires monitoring their populations over a lengthy time period and over a large area, enough to capture both climate variation and any immediate or delayed effects on survival,” said Bond. The team obtained nearly two decades of data on local rainfall, vegetation greenness, and temperature during Tanzania’s short rains, long rains, and dry season, and then followed the fates of 2,385 individually recognized giraffes of all ages and sexes over the final 8 years of the two-decade period. Surprising effects of temperature on giraffe survival The team had predicted that higher temperatures would hurt adult giraffes because their very large body size might make them overheat, but higher temperatures positively affected adult giraffe survival. “The giraffe has several physical features that help it to keep cool, like long necks and legs for evaporative heat loss, specialized nasal cavities, an intricate network of arteries that supply blood to the brain, and they radiate heat through their spot patches,” noted Derek Lee, associate research professor of biology at Pennsylvania State University, co-founder of Wild Nature Institute, and senior author of the study. However, Lee also pointed out that “temperatures during our study period may not have exceeded the tolerable thermal range for giraffes, and an extreme heat wave in the future might reveal a threshold above which these massive animals might be harmed.” Heavy rains may increase parasites while reducing nutritional value of vegetation Survival of giraffe adults and calves was reduced during rainier wet seasons, which the researchers attributed to a possible increase in parasites and disease. A previous study in the Tarangire region showed giraffe gastrointestinal parasite intensity was higher during the rainy seasons than the dry season, and heavy flooding has caused severe outbreaks of diseases known to cause mortality in giraffes, such as Rift Valley Fever Virus and anthrax. The current study also found higher vegetation greenness reduced adult giraffe survival, potentially because faster leaf growth reduces nutrient quality in giraffe food. Human pressure place additional stress on already declining populations Climate effects were exacerbated by the giraffe’s proximity to the edge of protected reserves, but not during every season. “Our findings indicate that giraffes living near the peripheries of the protected areas are most vulnerable during heavy short rains. These conditions likely heighten disease risks associated with livestock, and muddy terrain hampers anti-poaching patrols, leading to increased threats to giraffe survival,” said Arpat Ozgul, University of Zurich professor and study author. The team concluded that projected climate changes in East Africa, including heavier rainfall during the short rains, will likely threaten persistence of giraffes in one of Earth’s most important landscapes for large mammals, indicating the need for effective land-use planning and anti-poaching to improve giraffes’ resilience to the coming changes. How the Masai giraffe population has changed over 40 years in Tanzania’s Arusha National Park1/20/2023 Giraffes are Tanzania’s national animal and beloved around the world. Despite their popularity, however, populations of the Masai giraffe have declined by 50% since the 1980s to about 35,000 individuals, and they are now considered to be endangered. Masai giraffes are found in Arusha National Park in northern Tanzania and are an important part of the attraction of the park, contributing to the country’s economy. Urban development of Arusha city and agricultural expansion have caused Arusha National Park to be increasingly isolated from other protected areas in northern Tanzania, but the current status of giraffes in the park was not known. In a new paper published in the African Journal of Ecology, scientists from Pennsylvania State University, University of Zurich, and Wild Nature Institute enumerated individual giraffes in Arusha National Park to see how well these iconic megaherbivores were doing compared to 40 years ago. The only previously published data on the Masai giraffe population of Arusha National Park were from 1979 and 1980, 20 years after the park was established. In the new paper, scientists monitored individual giraffes in Arusha National Park from 2021 to 2022 to provide an update on the current population size, population sex and age structure, and movements. The giraffes were identified individually by their unique spot patterns. The scientists also collected DNA from dung samples to assess the genetic connectivity of the park’s giraffes with other giraffe populations in the region. The scientists documented a 49% population decline—similar to the overall decline of the Masai giraffe throughout its native range in Tanzania and southern Kenya—and changes in the age distribution, adult sex ratio, reproductive rate, and movement patterns relative to the previous study. Mitochondrial DNA analysis revealed genetic connectivity between Arusha National Park and other Masai giraffe populations east of the Gregory Rift Escarpment in northern Tanzania and south-eastern Kenya, providing evidence that Masai giraffe once moved widely across the landscape.

“Every giraffe population matters,” said Dr. Derek Lee, associate research professor at Pennsylvania State University, co-founder of the Wild Nature Institute, and the study’s lead author. He recommended that “the Arusha National Park giraffe population could be helped through community conservation efforts supporting indigenous communities outside the park that empower local law enforcement and provide tangible economic benefits of wildlife protection.” However, additional measures should be taken to secure the future of the giraffes in Arusha National Park. “We not only need to safeguard individual animals,” noted Dr. George Lohay, a geneticist from Pennsylvania State University and co-author of the study. “We also need to maintain and restore habitat connectivity with other populations to keep needed gene flow for genetic diversity.” Dr. Monica Bond, a postdoctoral research associate at University of Zurich, Wild Nature Institute co-founder, and senior author of the study, noted that protecting giraffes helps other animals as well. “The giraffes’ large body size and large space use needs make them particularly vulnerable to extinction,” she stated, “but actions to protect them will also benefit smaller species that share the same savanna habitat.” Lee, D. E., Lohay, G. G., Madeli, J.,Cavener, D. R., & Bond, M. L. (2023). Masai giraffe population change over 40 years in Arusha National Park. African Journal of Ecology, 00, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/aje.13115 Extra! Extra! Read all about it! Wild Nature Institute's 2022 Annual Report is available. We invite you to catch up on all that we accomplished in 2022, from giraffe photographic identification surveys and DNA collection across northern Tanzania, to our scientific publications, to celebrating World Giraffe Week at schools in Tanzania. We could not have accomplished these goals without the amazing and generous support of our donors and partners, and as always we are deeply grateful.

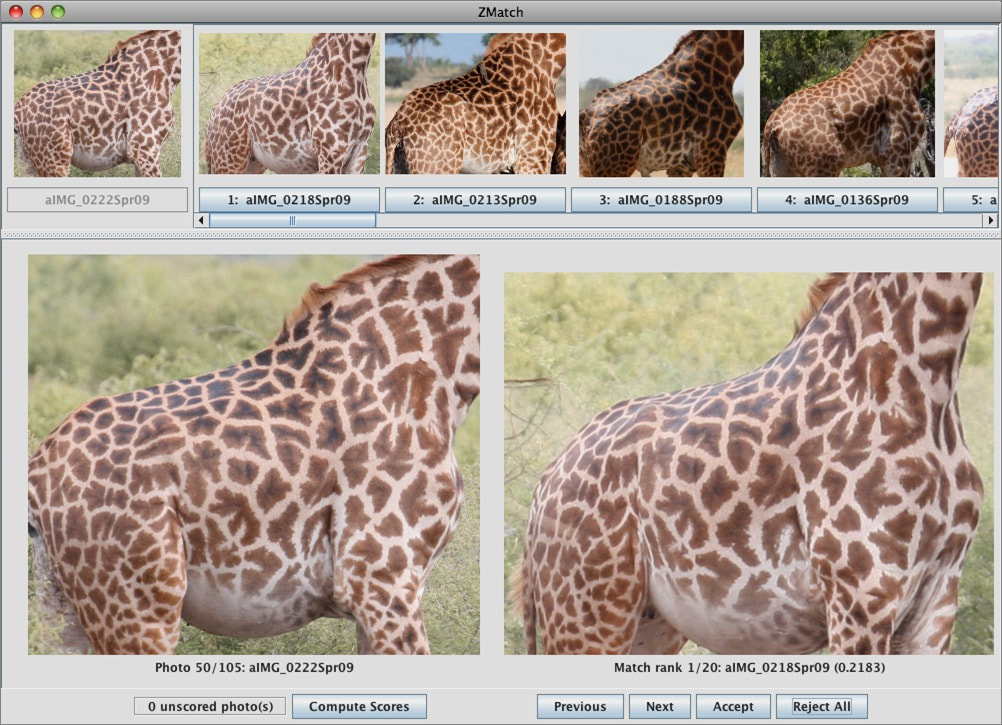

Giraffes are the perfect animal to study population dynamics and behavior of a large mammal using spot-pattern recognition, where natural born spot patterns provide every animal with a unique identifier scientists can use. Spot-pattern recognition is superior to tagging because it is non-invasive, the animals are never captured and affixed with a tag; the spots are permanent whereas tags are often lost; and we can identify and get data from every animal in our population, rather than just a few tagged animals. In our latest paper published today in Mammalian Biology, we reviewed 70 years of research on giraffes based on identifying individuals by their unique spot patterns. We describe our Masai Giraffe Project in the Tarangire Ecosystem of Tanzania, and explain how recognizing individuals by the patterns allows scientists to learn about births and deaths, movements, social structure, and health. We also provide recommendations for conservation actions based on what we have learned from the past 7 decades of research, so that we can safeguard a future for this magnificent mega-herbivore.

Animal coat patterns may have several functions, one of which might be to help individuals to recognize each other. In our new paper published this week in the Journal of Zoology, Phenotypic matching by spot pattern potentially mediates female giraffe social associations, we revealed that spot traits were individually variable among adult female giraffes in the Tarangire Ecosystem, and that females showed stronger associations with other females that had similar spot shapes. Our previous study found that spot shape was also similar between mother giraffes and their offspring, suggesting an effect of relatedness on both pattern similarities and female social relationships. Spot patterns of giraffes could be a visual cue for communicating and for recognizing related family members.

Happy World Giraffe Day and World Giraffe Week! Children and community members in the Tarangire region of Tanzania celebrate their national animal at a Giraffe Fun Day at Esilialei Primary School. Thank you as always to our funders for helping to make this celebration happen! To survive, animals must find nutritious food and drinking water—sometimes during long dry seasons or cold periods—and at the same time avoid being eaten. Plant-eating mammals with hooves for feet are an extraordinarily diverse group of animals and are critically important in East African savannas. Yet they must compete more and more with humans for space in a fast-changing world while also evading hungry lions, leopards, and other natural predators. A new study by scientists from the Wild Nature Institute, University of Zurich and Pennsylvania State University, published in the Journal of Mammalogy, investigated the habitat needs of a community of hooved-mammal species in the Tarangire Ecosystem of northern Tanzania, and how vegetation, water, presence of humans, and risks from predators influenced their use of these habitats. This was the first study of its kind in the Tarangire Ecosystem, which supports the ecotourism hotspot of Tarangire National Park and is the heart of Maasailand where cattle herders and wildlife have thrived together for centuries. Tarangire differs from other areas where wild ungulates have been intensively studied—like Serengeti National Park or Kruger National Park—in that Tarangire’s wildlife, cattle-keeping people, and farmers all share the landscape, and animals can move unimpeded because the entire region is unfenced. “Ungulates of different body sizes have different needs and threats,” said the study’s lead author Nicholas James, who conducted the research as a graduate student at University of Zurich. For instance, large ungulates like adult giraffes may have less to fear from natural predators but may face more danger from humans, and smaller animals may have more specialized food requirements. “We wanted to know what features draw each ungulate species to certain areas so we can pinpoint important habitat for each of those species,” James said. This information is important for land managers to maintain thriving populations of wild ungulates and keep the landscape healthy, which is the foundation of Tanzania’s important ecotourism economy. James and his co-authors counted and mapped six hooved mammal species in dry and rainy seasons over seven years in and around Tarangire National Park and the adjacent Manyara Ranch Conservancy, including unprotected village lands. The ungulates studied included the iconic, massive giraffe down to the little dik-dik—both of which specialize on eating leaves of woody plants—as well as the large, water-loving, grass-eating waterbuck, and three medium-sized antelopes that eat both woody-plant leaves and grass, the impala, Thomson’s gazelle, and Grant’s gazelle. The scientists looked at how the different species used areas depending on the type and greenness of plant food, the thickness of the bushes (where lions often lurk), and how far the areas were from rivers (which provide vital drinking water but also hide predators) and cattle herder settlements (where human disturbance is higher but the humans also keep away predators). The study highlighted the importance of food (vegetation) for all species, as well as nearness to year-round rivers for most but not all. Some species appear to be tolerant of human presence and even congregated close to cattle herder settlements, presumably because of lower predator densities there. The researchers found that antelopes that ate both grass and woody-plant leaves allowed them to avoid areas with high human activity while meeting their dietary needs. Importantly, the presence and number of herbivores were sensitive to short and long-term variation in rainfall suggesting they are vulnerable to drought. “We show that the focus of research and management should be directed towards the Tarangire Ecosystem’s free-flowing rivers and associated habitat along those rivers,” said Derek Lee, associate research professor at Pennsylvania State University and senior author of the study. “In dry landscapes like East African savannas, water resources are increasingly monopolized by humans, so protection of waterways in human-dominated landscapes, and ensuring sufficient access for wildlife is of primary conservation importance.” Another key finding of the study was that traditional cattle herders and some ungulate species can share the same space and thus appear to be compatible, so long as the human impacts remain relatively low.

Literature: James, N.L., Bond M.L., Ozgul A., and Lee, D.E. 2022. Trophic processes constrain seasonal ungulate distributions at two scales in an East African savanna. Journal of Mammalogy doi/10.1093/jmammal/gyac050 Wild Nature Institute is pleased to announce the publication of a new book co-edited by WNI scientists Drs. Derek Lee and Monica Bond, along with our colleague Dr. Christian Kiffner. The book is called “Tarangire: Human-Wildlife Coexistence in a Fragmented Ecosystem” and is published by Springer Nature. We pulled together academics studying humans and wildlife inhabiting the Tarangire Ecosystem of northern Tanzania , and asked them to contribute chapters. The Tarangire region, where WNI has been studying giraffes and other ungulates for the past 10 years, is remarkable in that the ecosystem is still ecologically functional. As we note on the final page of the book, Tarangire hosts hundreds of thousands of people, millions of livestock, large mines, booming towns, two major tarmac roads, and a patchwork of agricultural fields—and yet still supports one of the most significant long-distance migrations of wildlife remaining in the world, much of it taking place on community land. It also is home to one of the most important populations of giraffes in Tanzania, and therefore in the world. Wildlife numbers have declined historically, but the mere fact that many populations are stable, and some are increasing, despite all the odds, is testament to the singularity of the place, and demonstrates that humans and wildlife can indeed coexist. This edited volume summarizes multidisciplinary work on wildlife conservation in the Tarangire Ecosystem. By drawing together human-centered, wildlife-centered, and interdisciplinary research, it contributes to furthering our understanding of the often complex mechanisms underlying human-wildlife interactions in dynamic landscapes. By synthesizing the wealth of knowledge generated by anthropologists, ecologists, conservationists, entrepreneurs, geographers, sociologists, and zoologists over the last decades, this book also highlights practicable and locally adapted solutions for shaping human-wildlife interactions towards coexistence. It is written for students, scholars, and practitioners who are interested in reconciling the needs of human populations with those of the environment in general and large mammal populations in particular.

Wild Nature Institute’s Derek Lee and Monica Bond traveled to Tulsa Oklahoma for the Conservation on Tap event at the Tulsa Zoo. Breweries offered tastings of their finest craft brews, and all the proceeds benefited Wild Nature Institute’s research, education, and actions to conserve giraffes in Tanzania. Thanks so much to Tulsa Zoo, all the participating breweries, and all the attendees for standing tall for giraffes!

|

Science News and Updates From the Field from Wild Nature Institute.

All Photos on This Blog are Available as Frame-worthy Prints to Thank Our Generous Donors.

Email Us for Details of this Offer. Archives

July 2024

|

|

Mailing Address:

Wild Nature Institute PO Box 44 Weaverville, NC 28787 Phone: +1 415 763 0348 Email: [email protected] |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed