|

0 Comments

A new study, published today in The Condor Ornithological Applications, found that productive, high-quality Spotted Owl territories in southern California remained occupied and reproductive after severe wildfire burned through the area. This is important information for forest managers to understand that severe forest fire is not a significant threat to this old-growth associated species, as has been commonly asserted. Monica Bond, a co-author of the study said, "Here is another dataset that shows fire is not a significant threat to Spotted Owls. The US Forest Service is logging our public lands under the guise of protecting Spotted Owls from fire, but there is no evidence that fire is a danger to the species. However, logging has been proven to harm the owls. This mis-management of our public lands must stop."

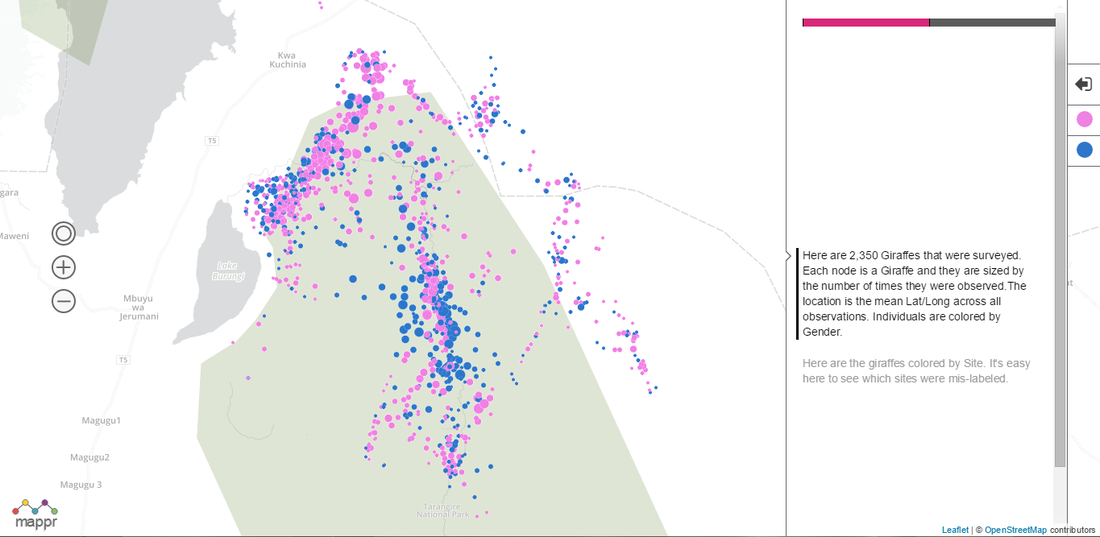

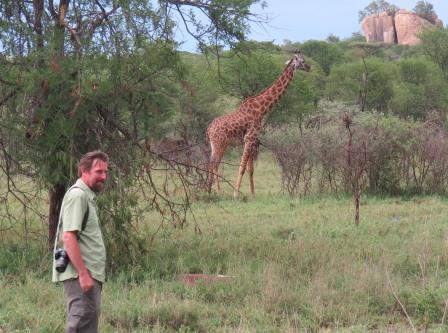

For the past 6 months, we have been surveying for wildlife in the region from Manyara Ranch up to the Northern Plains near Lake Natron. This is a critical area for the migration of wildebeest and zebra from Tarangire National Park, and it provides important habitat for resident animals like giraffe and another long-necked hoofed mammal, the gerenuk. The most numerous large animals we record (aside from cows and goats) are Grant's gazelles and plains (Burchell's) zebras, but we also regularly see giraffe, Thomson's gazelles, wildebeest, ostrich, gerenuk, dik dik, and impala. The landscape is truly magnificent, with sweeping views of several volcanoes, including the still-active Oldonyo Lengai, which means "Mountain of God" in the Maa language of the Maasai people who inhabit this area. The ash from Oldonyo Lengai makes the grasses in the surrounding area highly nutritious for herbivores, which is why ungulates migrate all the way from Tarangire National Park--a distance of over 100 kilometers--to give birth in the Northern Plains.

Derek Lee, co-founder of the Wild Nature Institute, just received his PhD in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology from Dartmouth College. Derek's dissertation is entitled "Giraffe Demography in the Fragmented Tarangire Ecosystem of Tanzania," and his adviser was Dr. Douglas Bolger. Congratulations Derek, and thank you Dr. Bolger! We look forward to continuing giraffe research and conservation work in Tanzania for many years to come.

Scott Streater, E&E reporter

Published: Thursday, April 30, 2015 California spotted owls did not abandon prime habitat that was scorched during the massive Rim Fire in 2013, according to a new study that argues against the Forest Service contracting to log fire-damaged trees near owl habitat in Stanislaus National Forest. The study, conducted by researchers with Hanover, N.H.-based Wild Nature Institute and published this week in The Condor: Ornithological Applications, found that within a year after the Rim Fire burned more than 257,000 acres, mostly in the Stanislaus forest in central California, the owls were occupying their historical territory even when the standing trees were completely scorched. "Many people thought that the owls would have abandoned these sites in droves because the fire was so massive," said Monica Bond, a biologist for the nonprofit Wild Nature Institute research group and the study's co-author. But while Bond said Forest Service officials have publicly referred to the 400-square-mile burn area as "nuked, a moonscape," these standing trees referred to as "snag forest" offer a rich habitat where the owls can perch and hunt rodents that are eating the seeds and leaves of shrubs that are numerous in burned areas, the study found. "Our results indicate that [forest] managers should not immediately assume Spotted Owls vacate burned sites," said the study, which suggests "that the most prudent course of action is to forgo logging activities in burned forests" within about a mile or so "of the post-fire nest or roost core to provide easily accessible potential foraging habitat within the larger home range." The study concluded, "Overall, we encourage land managers to recognize fire as a natural rejuvenating process of Sierra Nevada forests and to no longer assume burned forest is unsuitable California Spotted Owl habitat when planning and implementing management activities" in areas with known owl habitat. The study's conclusion could have policy implications for the Forest Service, which last year authorized logging to begin in the national forest to remove dead or dying trees scorched by the blaze -- the third largest wildfire in California's history. A coalition of environmental groups last fall filed a federal lawsuit against the Forest Service, asking the court to block the sale of any trees within roughly a mile of spotted-owl-occupied habitat. They argue that the spotted owl preferentially selects intensely burned forest when searching for food near its nests and roosts (Greenwire, Sept. 5, 2014). While that lawsuit is still pending, the U.S. District Court for the District of Eastern California did not approve an injunction halting the salvage logging activity, which began last summer and is set to resume again later this spring, said Rebecca Garcia, a spokeswoman for Stanislaus National Forest in Sonora, Calif. The Forest Service evaluated the impacts of logging the scorched trees in the national forest and last August approved a record of decision allowing 15,383 acres of salvage logging, as well as 26,890 acres of hazardous fuels treatments and the clearing of hazardous trees along 325 miles of roads. The study is the latest in an ongoing debate over commercial logging and the California spotted owl. The California spotted owl is not listed under the Endangered Species Act but is a "sensitive species" that environmental groups warned is in decline on Forest Service lands in the Sierra Nevada. Environmentalists have long argued that snag habitat is valuable. Native flowering shrub patches on the forest floor attract insects, birds and bats, and they provide habitat for small mammals that become food for the spotted owl. For the study led by the Wild Nature Institute, the researchers surveyed 45 known owl sites within the area affected by the Rim Fire, between late March and early August 2014. They inspected each site at least three times, and as many as 10 times, according to the study. The researchers found that 92 percent of the historical spotted owl territories within the burned area were occupied, including sites where fire killed most of the large trees surrounding the owls' nests and roosts. This conclusion supports years of research that fire does not have the same negative impact on owls as logging, because owls have evolved over millennia with wildfire as a natural disturbance and can still find foraging habitat in burned areas if they are not logged, according to the Wild Nature Institute. "Spotted owls like lots of big old trees, whether those trees are alive or fire-killed, and they can find prey in shrubby areas regenerating after fire," said Derek Lee, a quantitative ecologist with the Wild Nature Institute and the study's lead author. "Fire is not a threat to spotted owls, but logging is." Email: [email protected] |

Science News and Updates From the Field from Wild Nature Institute.

All Photos on This Blog are Available as Frame-worthy Prints to Thank Our Generous Donors.

Email Us for Details of this Offer. Archives

July 2024

|

|

Mailing Address:

Wild Nature Institute PO Box 44 Weaverville, NC 28787 Phone: +1 415 763 0348 Email: [email protected] |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed