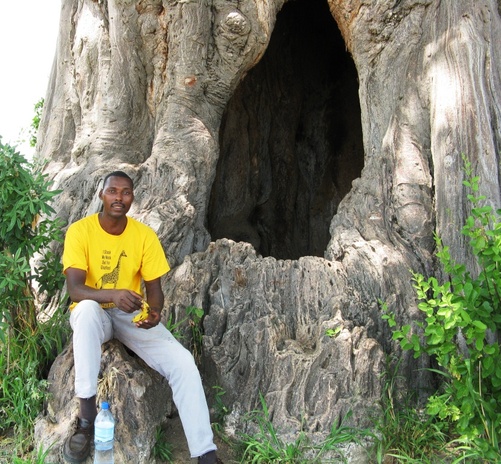

Tarangire National Park is world-famous for its high density of baobab trees, one of the most interesting and unusual trees on the planet. Monumental in size, bizarre in shape, and extraordinary in function, these trees are highly adapted to survive under quite extreme environmental conditions, including drought, fire, and the voracious and not-so-gentle appetites of elephants. Baobabs are undoubtedly the biggest trees in our study area. One of the largest baobab trees in Africa occurs on the coast of Kenya and its girth measures almost 30 meters! But they are not necessarily the most massive by volume – the larger baobabs actually have hollow trunks, or trunks filled with decomposing debris. Its great size is necessary to keep it standing, because its wood structure is not strong. In most other trees, the living tissue that transports water and nutrients is located between a tough, protective outer layer of bark and the softer internal wood. In the baobab, however, the living tissue comprises the entire trunk. There is no bark and there is no wood – it is all one.

Why would this be so? This unique structure ensures that fires and elephants cannot destroy all the living tissue. No matter how much an elephant gouges the tree trunk or rips off pieces with its tusks, or how intensive a fire burns, there is always living tissue behind the damaged area that continues functioning. The wood is also pithy, allowing the tree to uptake and store massive amounts of water from rainy season deluges through their shallow root system. This water-uptake system enables baobabs to maximize the time their leaves remain active before they dry up and fall off during the dry season (called “drought-deciduous”). Many animals seek out the baobab tree for shelter, including leopards and other smaller cats, and the trees are favorite nesting places for hornbills, birds of prey, and bees. Even giraffes will occasionally feast upon the leaves. Their lovely flowers (closed during the day to retain moisture) open at night and release a strong scent, attracting bushbabies and fruit bats seeking sweet liquid located in a juicy swelling in the flower stalk. As these mammals bury their faces in the flower to drink, the pollen brushes their muzzles. They carry the pollen to another flower and deposit it during their next meal, and the baobab flower is pollinated, leading to seed and a fruit pod – and eventually another extraordinary baobab tree.

0 Comments

We had a great TUNGO survey with Chena and Harper helping us. Enjoy these pictures from the trip. We are going out for another round of Tarangire Ungulate Observatory surveys for the next week. We will post an update when we return. Until then, here is a nice picture of a steenbok.

Imagine you are sitting under the shade of an Acacia tree, enjoying the beauty of the African savanna landscape. Suddenly you spot a small, hard ball of poop rolling along the ground, apparently of its own volition! Take a step closer, and you might catch a glimpse of one of the most important creatures in the savanna ecosystem – the dung beetle. Every day, millions of herbivores – including the ungulates that we are studying in the Masai Steppe Ecosystem – eat tons of grass, excreting vast amounts of seed-filled dung. Dung beetles disperse, feast upon, and live within these droppings, which provide a nutrient-rich food source for the beetles’ larvae. This may seem a lowly, rather unenviable lifestyle, but entomologists now understand that the savannah and many of its plants and animals completely depend upon the ecosystem services provided by dung beetles. More than 100 species of dung beetle have been recorded in Serengeti National Park alone, with different strategies in how they utilize the dung. “Roller” beetles create a ball of dung up to 40 times their body weight and can transport it up to 70 meters away, thus spreading nutrients far and wide. “Tunneller” beetles bury their balls of dung, helping the plant seeds within to germinate. Without these beetles, the ground would quickly be covered in a thick layer of dung, smothering the grasses that ungulates depend on for food. Even the lowliest members of an ecosystem play critical roles in the intricate web of life. The Sacramento Zoo has donated $2000 to support our Masai Giraffe Conservation Demography Project, and the Sacramento Chapter of the American Association of Zoo Keepers has donated $400 as well. Thanks So Much Sacramento Zoo! http://www.saczoo.org/

|

Science News and Updates From the Field from Wild Nature Institute.

All Photos on This Blog are Available as Frame-worthy Prints to Thank Our Generous Donors.

Email Us for Details of this Offer. Archives

July 2024

|

|

Mailing Address:

Wild Nature Institute PO Box 44 Weaverville, NC 28787 Phone: +1 415 763 0348 Email: [email protected] |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed