|

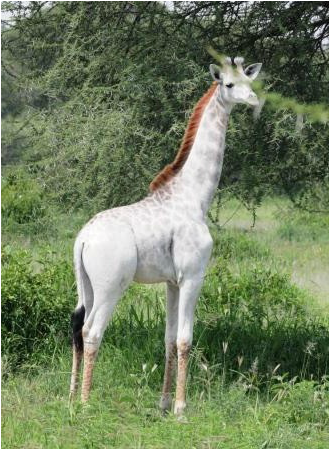

Last year we reported on our blog our sighting of a beautiful leucistic giraffe calf in Tarangire National Park. Her body surface cells are not capable of making pigment, but she is not an albino. We were lucky enough to resight her again this January, almost exactly one year later. We are thrilled that she is still alive and well. Below are photos of the leucistic giraffe calf, then and now. A local lodge guide christened her Omo, after a popular brand of detergent here. Alternative names are welcome, or vote for Omo as her moniker.

92 Comments

A new study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, has determined that the area burned by wildfires is unaffected by recent mountain pine beetle outbreaks.

Contrary to the expectation that a mountain pine beetle outbreak increases fire risk, this study shows no effect of outbreaks on subsequent area burned across the West. This study expands upon our own work in southern California, and work by other scientists, that found pre-fire insect- and drought-caused tree mortality does not influence forest fire severity. These results refute the assumptions that increased bark beetle activity has increased area burned or fire severity. Therefore, policy actions should focus on societal adaptation to the effects of warmer temperatures and increased drought. Wild Nature Institute scientist Derek Lee, who was not part of the PNAS study said,"Logging will not change fire behavior, our forests are naturally resilient, if we would just have the courage to leave them alone, they will self-regulate." In the western United States, mountain pine beetles have killed pine trees across 71,000 square kilometers of forest since the mid-1990s, leading to widespread concern that abundant dead fuels may increase area burned and exacerbate forest fire behavior. The false assumption that outbreaks raise fire risk is driving far reaching policy decisions involving logging that costs U.S. taxpayers hundreds of millions of dollars. Wild Nature Institute scientist Monica Bond, who was not part of the PNAS study said,"Far from being a threat, high-severity fire and insect outbreaks actually provide great benefits to forests and many wildlife species. Logging—including thinning in the name of fire reduction, and salvage logging of burned trees—is actually the greatest threat to our western US forest ecosystems." Watching a rhinoceros is like stepping back in time 5 million years. These behemoths, like giraffes, elephants, and hippopotamuses, are some of the few remaining “megaherbivores,” plant-eaters that weigh more than a ton and were once common throughout the world. Today's megaherbivores are mostly restricted to Asia and, especially, Africa. Like all megafauna, rhinos live a long time (up to 35 years in the wild), have slow population growth rates, low adult mortality rates, and few natural predators capable of killing adults. Their slow reproductive rates make their populations vulnerable to human overexploitation. Millions of years ago, more than 30 genera of rhinoceroses were found throughout Eurasia, North America, and Africa, but only 5 species in 4 genera survived into modern times. All 5 species now teeter on the brink of extinction. As we reported in an earlier blog, the mass extinction of megaherbivores in North America during the Pleistocene epoch reduced soil and plant fertility. The modern-day extinction of rhinoceros could similarly damage ecosystems. Black rhinos—the only species in Tanzania—have two horns, which grow continually from the skin at their base like human fingernails. The front horn is longer than the rear horn, males tend to have thicker horns, and females usually have longer and thinner ones (see photos below). The horn is made of thousands of compressed hair-like strands of keratin (same material as hair and fingernails), making it extremely tough, but it can be broken or split during fighting. Uncontrolled poaching for horns, used in Yemen for ceremonial dagger handles and in Asia for traditional medicine, decimated the rhino population in Tanzania to only 32 in 1995. The species remains critically endangered. Black rhinos are most easily seen in the Ngorongoro Crater, especially during the rainier months. We saw 11 rhinos on a recent trip to the Crater, and caught a glimpse of one male’s impressive penis. According to veterinarian and rhinoceros expert Dr. Nan Schaffer, a fully erect rhinoceros penis extends up to two and a half feet and is shaped like a lightning bolt. To accommodate it, the reproductive tract of the female rhino is also quite long, with many twists and angles of its own. The penis is curved backwards, allowing the characteristic rear-directed urination. Urine spraying is a common form of scent marking, both for males marking their territory, and also for females to signify to nearby bulls when they are in estrus. Spraying bursts can reach up to 3-4 meters away and males often follow a spray with vigorous horning of the urine-soaked soil and vegetation. Scent-marking is critical for communication, as rhinos have extremely poor eyesight. One way to help protect and restore rhinoceroses is to financially support bold, effective, grassroots organizations working to stop the poaching crisis. The best group in Tanzania is PAMS Foundation. PAMS works tirelessly to ensure a future for megaherbivores like elephants, rhinos, giraffes, as well as other animals suffering from poaching.

|

Science News and Updates From the Field from Wild Nature Institute.

All Photos on This Blog are Available as Frame-worthy Prints to Thank Our Generous Donors.

Email Us for Details of this Offer. Archives

July 2024

|

|

Mailing Address:

Wild Nature Institute PO Box 44 Weaverville, NC 28787 Phone: +1 415 763 0348 Email: [email protected] |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed