|

Mutualistic relationships between species--where each benefits from the other--are critical to ecological function and the maintenance of biological diversity. One interesting example of mutualism in the east African savanna is the relationship between the whistling-thorn Acacia tree (Acacia drepanolobium), large herbivores such as giraffes, and ant communities that live on the trees. Whistling-thorn Acacias reward ants that defend the trees from browsing herbivores. These trees produce hollow swollen thorns called "domatia" that house ants, and secrete nectar at the base of the leaves. There are four species of ants that compete for possession of host trees, but they vary in their defense of the tree against herbivores and other ants, and in their use of the tree's rewards of domatia and nectar. The most aggressive ant defender of the tree, Crematogaster mimosae, relies completely on domatia, whereas the less-aggressive ant defender C. sjostedti nests in cavities excavated by wood-boring beetles. A fascinating long-term study was conducted in Kenya examining the complex interactions between large herbivores, ant communities, and whistling-thorn Acacia. The researchers excluded some areas from herbivores, and then measured ant community dynamics and tree growth and survival. Their research, published in the journal Science (Palmer et al. 2008), found that when large herbivores were excluded, the trees produced less nectar, resulting in smaller colony sizes of their most active defender, the nectar-dependent C. mimosae. As numbers of C. mimosae decreased, the numbers of their competitor C. sjostedti increased -- but these ants actively facilitated attack of host trees by wood-boring beetles to make nesting cavities. The result? A dramatic reduction in growth and survival of the Acacia trees due to the attacks by wood-boring beetles. Counter-intuitively, trees in areas without large herbivores like giraffes ultimately suffered twice the mortality of trees in areas with large herbivores! The authors noted: "The large herbivores typical of African savannas have driven the evolution and maintenance of a widespread ant-Acacia mutualism and ... their experimentally simulated extinction rapidly tips the scales away from mutualism and toward a suite of antagonistic behaviors by the interacting species ... In the absence of large herbivores, reduction in host-tree rewards to ant associates results in a breakdown in this mutualism, which has strong negative consequences for Acacia growth and survival. Ongoing anthropogenic loss of large herbivores throughout Africa may therefore have strong and unanticipated consequences for the broader communities in which these herbivores occur." Yet another reason to save giraffes! Nature's web of life has evolved over millions of years, and when we mess with this delicate and complicated balance, we create serious adverse consequences for biological diversity.

0 Comments

This week during our surveys in Lake Manyara National Park, we were excited to see a baby elephant that we guessed was no more than an hour or two old. He was born in a dry, sandy riverbed, making a soft bed to rest and gather his strength to stand up and nurse for the first time. Three large female elephants (the mother and related females) formed a triangle around him, fiercely guarding the vulnerable newborn. After a while, the mother gently helped the baby to stand up, using her foot to raise him and trunk to steady him. He was extremely wobbly on his feet and fell several times. Immediately upon standing up, the baby elephant raised his head and made suckling motions. The females guided him to his mother's teat and we applauded when he took his first drink of nutrient-rich milk.

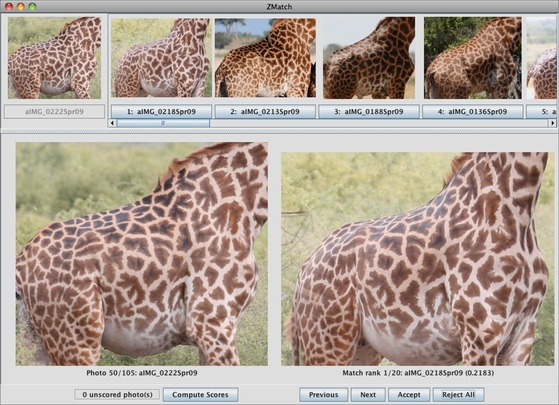

Let the forests burn - their ecology depends on it! by Monica L. Bond, Chad T. Hansen & Dominick A. Dellasala Forest fires are invariably portrayed as fiercely destructive environmental calamities. But for the native forests of the American West, large fires are essential to ecological renewal. Contrary to the mantras of logging companies and forest service officials, we suppress them at our peril. READ THE FULL ARTICLE HERE: http://www.theecologist.org/campaigning/2380295/let_the_forests_burn_the_ecology_depends_on_it.html  We are about to start another survey for giraffes in the Greater Tarangire Ecosystem as part of our Masai Giraffe Conservation Project. Scientists from the Wild Nature Institute and Dartmouth College conduct three giraffe surveys per year, just after each of the three rain seasons in Tanzania. Each survey consists of driving hundreds of kilometers and photographing every giraffe we see, and then doing it all over again one more time! The whole survey takes about a month, during which we camp in the bush at the end of each long day of searching for giraffes from sunup to sundown. It is tough, hot, often muddy, and plagued by tsetse flies, but we are privileged to be able to work on such an intimate level with the tallest and one of the most beloved animals on the planet. Giraffe have fur patterns that are unique to each individual, much like a human fingerprint. At the end of each survey, we have at least 1,000 photographs of fur patterns to process and match with photos taken during previous surveys. We use a pattern-matching software program called WildID developed at Dartmouth College. The picture below shows the interface of the program. We put all this information together into a database, do some statistical analyses, and ultimately estimate survival and reproduction in different parts of our study area and at different times of the year. Our objective is to understand why survival and reproduction might be higher or lower in one area or during different seasons. We will use this information to develop effective conservation measures for giraffes in the threatened Tarangire Ecosystem. One of the great aspects of the Masai Giraffe Conservation Project is that we never have to capture any giraffes to identify them. The "photographic" capture method is non-traumatic for the animals and far less expensive for the researchers. We are able to track more than 1,500 individual giraffes, which would be nearly impossible if we had to capture them all, or to identify them all by eye without the aid of a computer. This is all thanks to digital photography and pattern-recognition software. Of course, many thanks also to our funders and partners, especially Dartmouth College, Sacramento Zoological Society, Columbus Zoo, Safari West, Cleveland Zoological Society and Cleveland Metroparks Zoo, Cincinnati Zoo, the American Association of Zoo Keepers, the Explorers Club, and many private donors! We truly couldn't do the work without you!

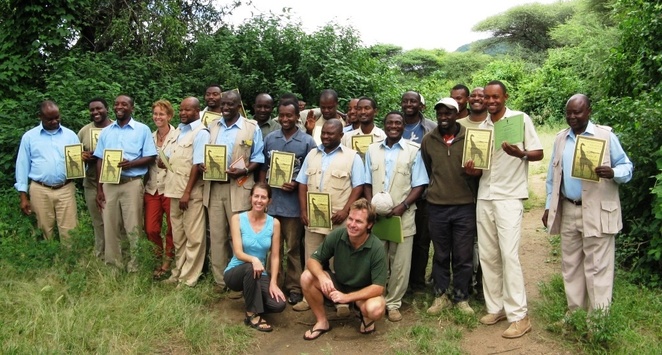

Monica spent the past weekend at Lake Manyara National Park helping the Interpretive Guides Society (IGS) to accredit Tanzanian safari guides. IGS is a project of the PAMS Foundation. The main objective of IGS is to help members improve their knowledge as professional naturalist guides. To be accredited, guides undertake two or more weeks of field training, are tested on their knowledge of various subjects including birds, plants, invertebrates, and mammals, and receive certificates for each subject they pass. Standards are set by the International Ranger Federation, the African Field Guides Association, and the IUCN World Commission on Protected Areas. This is a great way for guides to demonstrate their knowledge of the wondrous ecology and biodiversity of the African savanna and to raise the bar for all Tanzanian safari guides. We are happy to be a part of this worthwhile program.

A group of our colleagues recently visited the area burned last year by the Rim Fire in the Stanislaus National Forest. This was the largest wildfire in recent years, but as always, the forest is quickly rebounding back to life. Despite being a very dry winter, and despite the apocalyptic descriptions of the Rim Fire in the media, post-fire regeneration is already apparent. Wildflowers and wildlife abound, and new tree seedlings are already emerging. Even many trees that looked dead last year are flushing with new green growth. This is some of the very best habitat for many rare fire-dependent plants and animals. Salvage logging and so-called "restoration" will utterly destroy this ecological treasure trove.

|

Science News and Updates From the Field from Wild Nature Institute.

All Photos on This Blog are Available as Frame-worthy Prints to Thank Our Generous Donors.

Email Us for Details of this Offer. Archives

July 2024

|

|

Mailing Address:

Wild Nature Institute PO Box 44 Weaverville, NC 28787 Phone: +1 415 763 0348 Email: [email protected] |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed