Wild Nature Institute scientist Dr. Derek Lee has co-authored with Dr. Megan Strauss a publication on "Giraffe Demography and Population Ecology" that was published this week by Elsevier Press as a Reference Module in Earth Systems and Environmental Sciences. Population ecology studies the processes that cause the number of organisms in a population to increase or decrease. Population size through time reflects the combined outcome of three demographic processes: reproduction (births), survival (or its inverse, mortality), and movement (the combination of immigration and emigration). This article summarizes current knowledge of demography and population ecology of giraffes (Giraffa camelopardalis) and provides a framework for using population models when developing and evaluating conservation and management efforts for giraffes (or other large herbivore species). For conservation to succeed, it is critical that we are able to detect changes in population size and the demographic processes in the population, and also we must learn how to effect change in population size by managing specific demographic components. Learn more about how Wild Nature Institute's giraffe research is helping protect these amazing animals. The paper is available from Science Direct, or by request from the author

0 Comments

Wildlife Clubs around Tarangire recently had a lesson about Giraffes, the national animal of Tanzania, using the giraffe-themed environmental education materials developed by Wild Nature Institute and PAMS Foundation. These high school students appreciate that wildlife conservation is important to Tanzania's ecology, economy, and culture. Giraffes are becoming endangered throughout Africa, the only continent where they live, due to habitat loss and illegal killing called poaching. Wildlife-based tourism is the largest sector in Tanzania's economy and as a result, Tanzania has 32% of it's land in protected areas. The students are participating in Wildlife Clubs as an extra-curricular activity because they want to learn more. The core of our giraffe-themed conservation education project is Juma the Giraffe, and we developed some great teaching resources to go along with the book. We also printed an awesome poster explaining how wonderfully weird giraffes are that was designed by David Brown and Chris Barela. Wild Nature Institute's giraffe research is helping current and future conservationists like these students to understand how people and giraffes can live together for the benefit of all.

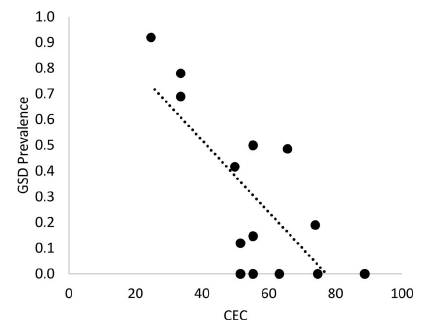

Lesions such as these on the forelimbs indicate giraffe skin disease. Lesions such as these on the forelimbs indicate giraffe skin disease. New research from Wild Nature Institute scientists published today in the Journal of Wildlife Diseases documented 'Soil correlates and mortality from giraffe skin disease (GSD) in Tanzania.' Giraffe skin disease is a disorder of the skin that is characterized by crusty lesions on the posterior forelimbs of adult Masai giraffe. Monica Bond, lead author of the study, said, "Identifying ecological correlates of a pathogen helps wildlife veterinarians and managers understand risk factors, and data from individually identified animals reveal whether the disease affects survival. This is the most recent step in our ongoing investigations into this emerging disease." The disease was first reported in 2000 in Ruaha National Park in central Tanzania. Previous work by Wild Nature Institute scientists found an interesting spatial pattern in the prevalence of the disease. The latest results built on that earlier finding and found giraffe skin disease was most prevalent on low fertility soils (as measured by cation exchange capacity or CEC, a common measurement of soil fertility). If parasites such as nematodes or tsetse flies are involved in giraffe skin disease, differences in soil may influence ground-dwelling life stages. Soil characteristics may also impact the nutritional status of giraffes through vegetation quality, thus affecting their susceptibility to the disease. "We found no mortality effect of giraffe skin disease in Tarangire National Park," said Bond, "indicating that currently giraffe skin disease is unlikely to warrant immediate veterinary intervention in this park." Movement of infected giraffe remains an unexplored aspect of GSD effects, but limited mobility could lead to lower survival or reproduction if climate, habitat, or predation factors change from current conditions in Tarangire. Monitoring in Tarangire will continue to ensure early detection if GSD-afflicted animals begin to show signs of increased mortality or other negative effects.

Learn more about Wild Nature Institute's Masai giraffe research and conservation work at www.wildnatureinstitute.org/giraffe.html  These large-diameter old-growth trees marked for logging in a US Forest Service fuels reduction project are typical of what is often described as 'thinning'. Logging like this, done under the pretense of fire risk reduction, is the reason Spotted Owl populations are crashing in National Forests, scientists say. Credit: Wild Nature Institute These large-diameter old-growth trees marked for logging in a US Forest Service fuels reduction project are typical of what is often described as 'thinning'. Logging like this, done under the pretense of fire risk reduction, is the reason Spotted Owl populations are crashing in National Forests, scientists say. Credit: Wild Nature Institute Monica Bond has spent the past 15 years studying spotted owls and forest fire. This week, Bond published an article summarizing existing science about what happens to spotted owls when forests burn, in the hope of averting a major US forest management policy disaster. US Forest Service (USFS) manages 11 million acres of public forest land in California's Sierra Nevada. The USFS has a new California spotted owl conservation strategy and is revising its forest management plans for Sierra Nevada national forests. These documents will guide how national forests are managed for the coming decades, and they are deeply misinformed about fire. The status of spotted owls tells the USFS how its management activities affect old-growth species. Since 1993 when the USFS began managing for California spotted owl habitat, populations of spotted owls have crashed on USFS lands. In contrast, spotted owl populations are stable in National Parks Service (NPS) lands. Both USFS and NPS lands have wildfires, but NPS lands are not logged. Logging on 1.2 million acres of USFS land in the Sierra Nevada between 1994 and 2014 is driving spotted owl declines. In Bond's summary paper[1], published by Elsevier Press as a Reference Module in Earth Systems and Environmental Sciences, she presents a data-driven narrative describing how forest fires, including big, severe megafires, have no strong negative effects on spotted owl populations. For example, in the largest and most comprehensive Sierra Nevada study to date[2], burned and unburned owl territories had the same probability of being occupied—even when about a third of the territories' area burned at high severity. "The lack of effect was remarkable because we found it repeatedly," said Bond. "We kept investigating different aspects and the story didn't change. Owls were harmed by logging, not by fire." These results make perfect sense in light of the history of the Sierra Nevada. Forest fire in the Sierra is typically mixed severity, meaning it includes some large patches of high severity fire, and is as natural and necessary to forest health as rain or sunshine. "The increased abundance and diversity of plants and animals in high severity burns tells us the Sierra Nevada's flora and fauna evolved with regular high severity fires." said Dr. Richard Hutto of University of Montana's College of Forestry and Conservation. However, Bond's results are troubling to the USFS and scientists on the USFS payroll. The new California spotted owl conservation strategy was written entirely without consulting Bond. A forest oversight organization asked the USFS to include her, but those requests were ignored. The USFS gets billions of dollars each year to fight fires, and millions more to administer sales of public lands trees to timber companies under the pretence of reducing fire risk. The three studies that examined spotted owl responses to logging all showed negative impacts from fuels reduction thinning. Thirteen scientific papers found no strong negative effects of high-severity fire on owl populations. Yet the USFS plans promote logging under the pretence that logging will save the owls from fire. Bond concluded, "There is a US forest policy train, about to leave the California station, which aims to promote widespread logging on public forests. The logging will be expensive, ineffective at stopping wildfire, and ecologically damaging, and it will be paid for by the taxpaying citizens of the USA. We must change the track." More information: [1] Bond ML (2016) The Heat Is On: Spotted Owls and Wildfire. Reference Module in Earth Systems and Environmental Sciences, dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-409548-9.10014-4 [2] 11 years of occupancy data from 41 burned breeding sites before and after 6 large fires, were compared with 145 long-unburned control sites during the same period (Lee et al. 2012). Read at: http://phys.org/news/2016-08-degrading-national-forests.html#jCp Juma the Giraffe is our wonderful children's book, and we offer free teaching resources to help guide discussion about the story and educate children and adults about giraffes.

Get a poster, matching game, mask-making pattern, and much more at www.JumaTheGiraffe.com The Amazing Migration of Lucky the Wildebeest Video Book

To reach a broader audience and make environmental education more entertaining, we have turned our Lucky the Wildebeest and Juma the Giraffe children's books into video books. The conservation lessons in Juma and Lucky are now accessible to every Tanzanian in English, Swahili, and Masai. The video book movies will be shown at rural villages around Tanzania as part of our Sinema Leo Environmental Education Roadshow. The roadshow is building pride in Tanzania's wildlife resources among an audience that has no access to national parks, very low literacy, and little access to outside entertainment.

(Post Updated Jan 2019.) A paper by Gavin Jones et al. "Megafires: an emerging threat to old-forest species" claims to describe negative effects of the 2014 King fire on California spotted owl occupancy and space use. There are several papers by other authors documenting how severe fire has little or no effect on spotted owl occupancy, and that they forage in high severity patches preferentially or in proportion to availability (Lee 2018). Jones et al. (2016) claim their data describe a strong negative impact of severe fire on spotted owls. The paper has fatal flaws in their analyses that render their results and discussion unreliable.

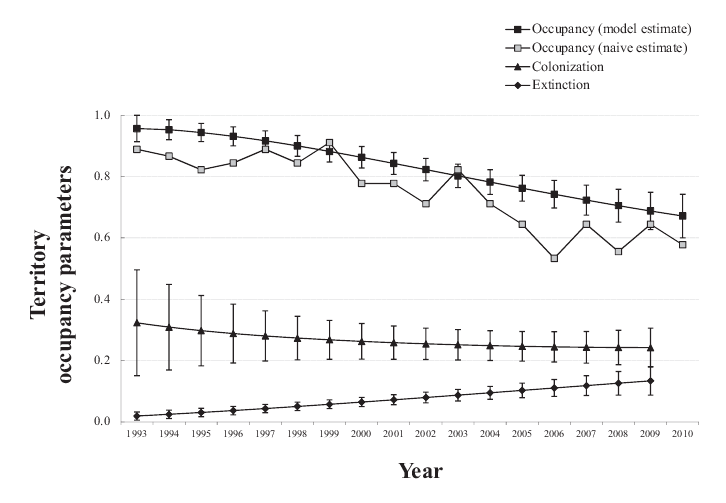

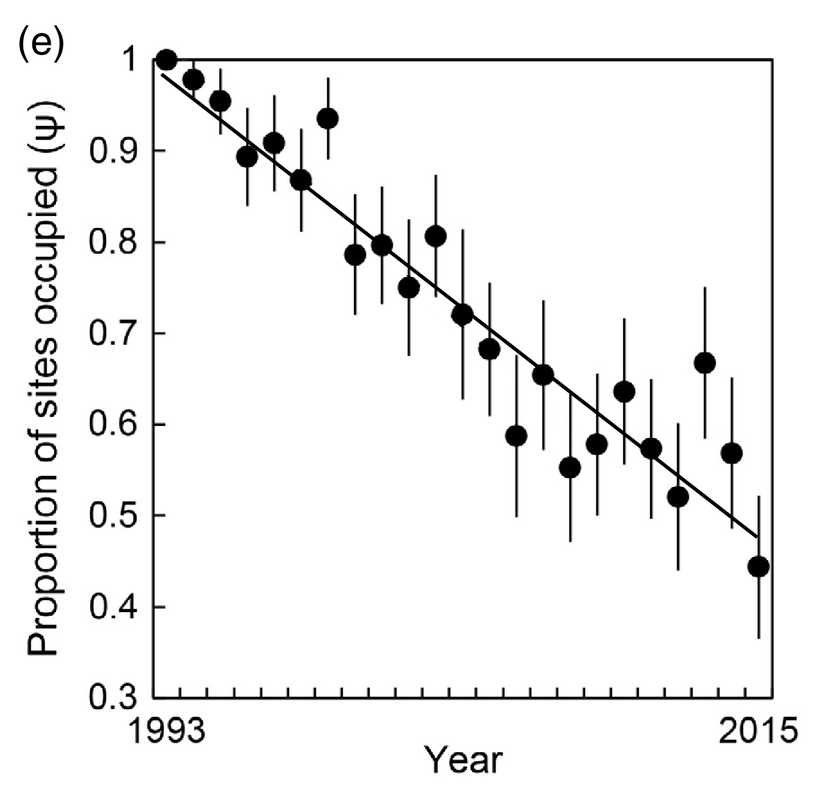

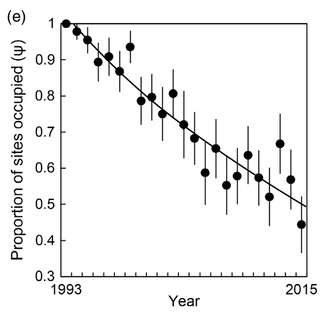

The population is in freefall, yet the authors compared their 1 year of post fire data against the mean of all previous years without accounting for the temporal trend in colonization and extinction. The observed long-term decline in annual site occupancy probability was the result of documented long-term trends of decreasing site colonization probability and increasing site extinction probability unassociated with fire (Tempel and Gutiérrez 2013). Jones et al. (2016) clearly described their method of partitioning their data into before-after and control-impact groups using only two dummy variables, and the first paragraph of their results and discussion compared estimates of extinction probability and occupancy probability from 2015 (one year post-fire) against the mean probability for all previous years. Clearly, Jones et al. (2016) did not account for the significant pre-fire temporal trends in colonization and extinction rates during their site occupancy analyses. This omission of temporal trends means their result for 2015 is due to the fact that this single year of post-fire data was the last year in the dataset, and should not be attributed unequivocally to the King fire. A simple linear trend of occupancy probabilities from 1993–2014 intersected the +1 SE error bar of the 2015 estimate (see below). This indicates that site occupancy in 2015 was not significantly different from the occupancy probability predicted for that year by the observed declining occupancy trend during the 22 pre-fire years. Jones et al. did a separate post-hoc analysis of trend in occupancy, but that was not included in the dynamic occupancy modelling. Including a pre-fire trend in the analysis would swamp the effect the authors attributed to fire. The temporal trend graphs Jones et al. should have presented and included in their dynamic occupancy analysis were the linear or quadratic trend (most likely the quadratic trend based on WebTable4)

Wildfire has more benefits than costs for spotted owl (Strix occidentalis) populations, according to a quantitative meta-analysis of forest wildfires, including “megafires” (Lee 2018). The best available summary of research on spotted owls and fire is Lee (2018)—the only systematic review and quantitative meta-analysis to date regarding spotted owls and mixed-severity fire (5–70% of burned area was comprised of high-severity fire patches with >75% mortality of dominant vegetation). Lee (2018) analyzed all studies of spotted owls (all three subspecies) in relation to mixed-severity fires that had not been subjected to post-fire logging. Fifteen papers reported 50 effects from fire that could be differentiated from post-fire logging. Meta-analysis of mean standardized effects (Hedge’s d) found only one parameter was significantly different from zero, a significant positive foraging habitat selection for low-severity burned forest. Multi-level mixed effects meta-regressions (hierarchical models) of Hedge’s d against percent of study area burned at high severity and time since fire found: a negative correlation of occupancy with time since fire; a positive effect on recruitment immediately after the fire, with the effect diminishing with time since fire; reproduction was positively correlated with the percent of high-severity fire in owl territories; and positive selection for foraging in low- and moderate-severity burned forest, with high-severity burned forest used in proportion to its availability, but not avoided. Spotted owls were usually not significantly affected by mixed-severity fire, as 83% of all studies and 60% of all effects found no significant impact of fire on mean owl parameters. It is important to clarify that instances of upwardly biased occupancy rates from false positives (e.g. Berigan et al. 2019) do not have any bearing on the effect size as analyzed in Lee (2018). False positives occur at all sites, regardless of level of burn severity (Berigan et al. reported no difference in false positive rates by burn severity), thus the effect size remains the same even if absolute occupancy rates might be upwardly biased. Contrary to current perceptions and recovery efforts for the spotted owl, mixed-severity fire does not appear to be a threat to owl populations; rather, wildfires as they have been burning in recent years appear to have more benefits than costs for spotted owls.

The Jones et al. study is one of only 3 examples of severe fire having a strong negative effect on spotted owls. The study was funded by the US Forest Service, and California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, groups with a financial interest in promoting thinning logging of our forests in the name of protecting them from severe fire.  Our study was published as the Editor's Choice article in the most recent issue of the Journal of Mammalogy. We found that even in national parks where wildlife are presumed to be safe and protected, vital rates of survival and reproduction varied widely. Dr. Derek Lee, Principal Scientist of the Wild Nature Institute and lead author of the study said, "People often assume every national park is successfully protecting the wildlife there, but we found not all parks are the same for giraffes." The study examined reproduction, adult survival, and calf survival, and found that all of these vital rates varied among the study sites. However, the most important factor determining whether a population was growing or declining was the same everywhere. "In northern Tanzania, and across the continent, adult female survival made the greatest contribution to local population growth rates, and lower adult female survival was related to human-caused effects" said Lee. The study indicates that protected areas, including national parks, cannot assume they are effectively saving wildlife, but should closely monitor their populations to ensure the species under their care are truly benefiting.

Dead Trees are Vital

Dead trees can remain standing for decades or more and a standing dead tree—known as a "snag"—provides great habitat for wildlife. Birds and mammals make their homes in openings carved within snags, while wood-boring insects that feed on snags provide the foundation of the food chain for a larger web of forest life, akin to plankton in the ocean. With so much life abounding, it doesn't seem right to call a snag "dead." We commonly associate that word with meaning the end of one's useful life and yet when a tree becomes a snag, it actually reaches a pinnacle of its beneficial role in the ecosystem. In other words, snags are a vital and vibrant part of the forest. When many snags are created together in what is known as a "snag forest," it produces some of the highest levels of native biodiversity of any forest type. Some forest animals, such as black-backed woodpeckers, depend on finding places with large swaths of snags. Unfortunately for them, unlogged snag forests have become quite rare. The Deficit of Dead Trees From the perspective of the timber industry, a snag in the forest is a waste, so timber companies and the Forest Service have spent decades cutting down snags as quickly as possible. As a result, there is now a significant lack of snags in our forests and this shortage is harming woodpeckers, owls and other forest wildlife. For them, the recent pulse of snag creation is good news. At first glance, 66 million dead trees may seem like a very large number, but it is important to remember that there are 33 million acres of forest in California, so the total effect of the recent pulse of tree mortality has been to add an average of only two snags per acre. To put that number in perspective, forest animals that live in snags generally need at least four to eight snags per acre to provide sufficient habitat and some species require even more snags. For example, California spotted owls use forests with eight to twelve snags to nest and rest and they prefer even higher levels of snags in the areas where they gather their food. And black-backed woodpeckers depend on snag forests with at least several dozen dead trees per acre. These points and many others were addressed in a letter from scientists to California Gov. Brown in February. Cashing in on Fear of Fire Despite the ecological benefits from the recent pulse of tree mortality, logging advocates have been eager to cut down the snags. In attempting to sway the public to support large-scale logging, they have not highlighted the wildlife habitat created by these snags or the overall snag deficit, but instead they have stoked fears that dead trees will cause severe wildfires. This claim is generally presented by portraying the trees only as "fuel" for fire. Depicting trees solely as "fuel" is a simplistic and misleading approach that reduces the natural complexity of the forest to a single dimension, resulting in erroneous assumptions about what really occurs. In fact, dozens of published scientific studies of what actually happens when beetle-affected areas burn show that dead trees do not cause severe fires. One recent study even found that areas with tree mortality burn at lower severity than green tree forests. Dr. Dominick DellaSala of the Geos Institute recently published a synthesis of this research and concluded, "There is now substantial field-based evidence showing that beetle outbreaks do not contribute to severe fires nor do outbreak areas burn more severely when a fire does occur." The results of the field research are inconvenient for those who try to use tree mortality as a justification for more logging. For example, U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack, who oversees the Forest Service, made no mention of these studies in his June press release about the California tree mortality. Instead, he falsely claimed that the tree die-offs "increase the risk of catastrophic wildfires" and then he used that claim to lobby for increased funding for his agency. The biomass power industry in California is also trying to cash in on this fire scare regarding dead trees. Biomass power facilities generate electricity by burning trees and other vegetation. This process is remarkably inefficient, with biomass burning facilities contributing to global warming by emitting more carbon per unit of energy produced than coal or natural gas facilities. (Moreover, in contrast to biomass power, renewable energy sources that don't burn carbon—such as roof-top solar—have no emissions). Biomass power is also economically inefficient, requiring substantial taxpayer and ratepayer subsidies, as well as regulatory loopholes, to keep biomass facilities in business. Thus, the current use of fear of fire to try to justify subsidized logging of snags to fuel biomass facilities is bad news for the climate and taxpayers, as well as for forest ecosystems. A New Understanding of Forest Diversity Rather than allowing logging proponents to exploit fear and misinformation about fire, we have a collective opportunity to learn from the current pulse of tree mortality and develop a greater understanding of the full diversity of California's forests. Dead trees, including large patches of snags, are a vital part of the forest. We should appreciate them, along with the natural processes that create them, such as beetles and wildfires. While forest protection efforts have historically focused on green trees, forests come in a variety of colors that also deserve protection, including trees with brown needles and trees with blackened bark. Their diversity provides the basis for a diversity of forest life. reprinted from EcoWatch Aug 06, 2016 By Douglas Bevington Douglas Bevington is the forest program director for Environment Now and the author of The Rebirth of Environmentalism: Grassroots Activism from the Spotted Owl to the Polar Bear (Island Press, 2009). Original article available at: http://www.ecowatch.com/dont-get-burned-by-misinformation-about-dead-trees-and-wildfire-1957452382.html What happens when Juma the baby giraffe sees his reflection in a water hole?

At JumaTheGiraffe.com you will find:

|

Science News and Updates From the Field from Wild Nature Institute.

All Photos on This Blog are Available as Frame-worthy Prints to Thank Our Generous Donors.

Email Us for Details of this Offer. Archives

July 2024

|

|

Mailing Address:

Wild Nature Institute PO Box 44 Weaverville, NC 28787 Phone: +1 415 763 0348 Email: [email protected] |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed