|

July 27, 2018

by George Wuerthner Published today in CounterPunch. “What but the wolf’s tooth whittled so fine the fleet limbs of the antelope?” wrote the poet Robinson Jeffers. Jeffers encapsulated the idea that evolutionary processes shape all plants and animals. Unfortunately, far too many in the Forest Service and the collaboratives that work with them fail to understand this basic idea—a “healthy” forest is one with many sources of mortality. Chainsaws are no substitute for natural processes. Recently on a collaborative/forest service field tour, participants were shown some fir trees with root rot. The group was told that the forest was “too dense” and thus the trees had become susceptible to root rot. The solution, of course, was to log (read kill) the fir trees so they would not succumb to root rot and die. When I asked the collaborative members and agency personal assembled, “What was the ecological role of root rot in the ecosystem?”, I got perplexed blank stares. It appeared that no one had ever considered such a question. Yet here they were anxious to log the forest based on the assumption that root rot killing trees was something to control or remove from the forest ecosystem. Among the ecological values that root rot may provide to the forest ecosystem is a natural thinning of trees (unlike logging/thinning that lost money, root rot does this at no cost to taxpayers). Root rot selects for those trees less adapted to current and future climatic conditions, plus creates snags and dead wood that is critical to many wildlife species. The snags store carbon, and when trees fall over, they establish hummocky mounds that result in micro-sites for plants and animals. The issue of root rot is a good example of where the Forest Service and collaborative members fail to see the forest (ecosystem) through the trees. Throughout the field trip, I was told the goal of logging was to “restore” forests so the trees would be “resilient” and less vulnerable to evolutionary processes like wildfire, drought, mistletoe, bark beetles, and root rot. But there is much more to a forest ecosystem than trees. Whether implicitly acknowledged, the focus on trees represents an Industrial Forestry paradigm that views trees as fodder for wood products. For many species of plants and animals, dead trees are critical to their survival. For instance, some 45% of all birds rely on snags for feeding, nesting, and rooting. Bats find shelter under the bark of dead trees. Small mammals from voles to marten hide beneath or inside downed logs. And some 50% of the aquatic habitat in small to medium sized streams is the result of fallen logs in the water. Most foresters will acknowledge grudgingly that some limited mortality from wildfire, drought, root rot, bark beetles and other natural agents may be acceptable, but they seldom promote the idea that these drivers of evolution are critical to the “health” of our forest ecosystems. Just as wolves help to maintain healthy elk and deer herds, other evolutionarily processes like wildfire, bark beetles, mistletoe, and root rot maintain healthy forest ecosystems. However, the Forest Service is focused on managing trees, not ecosystems. What they are doing is “restoring” the “structure”, not the evolutionary processes that have for millennia shaped and honed our forest ecosystems. The way you build “resilience” into the forest is by protecting, preserving and enhancing the ecological and evolutionary processes that have created the forest. Nature is much better at selecting which trees should survive than a forester with a paint marking can. If we wish to build resilience into our forests, we must maintain the ecological and evolutionary processes that “whittles” the ecosystem. George Wuerthner has published 36 books including Wildfire: A Century of Failed Forest Policy. He serves on the board of the Western Watersheds Project.

0 Comments

Wildfire Management Designed to Protect Spotted Owls May Be Outdated

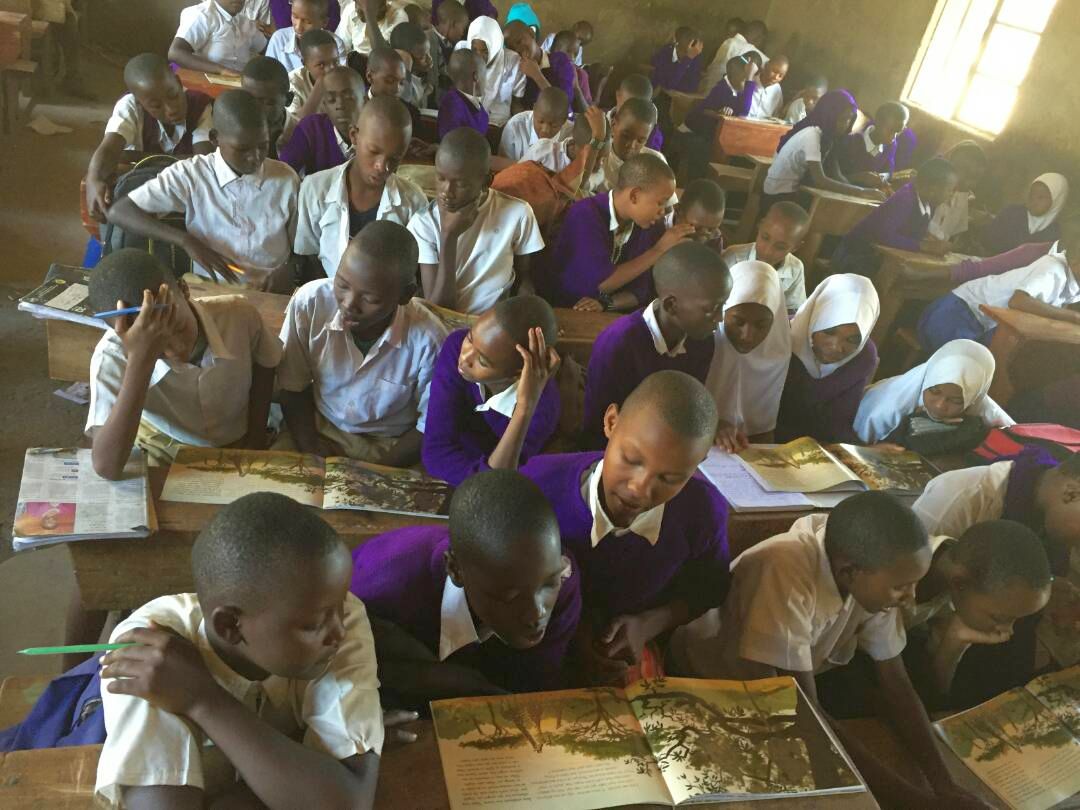

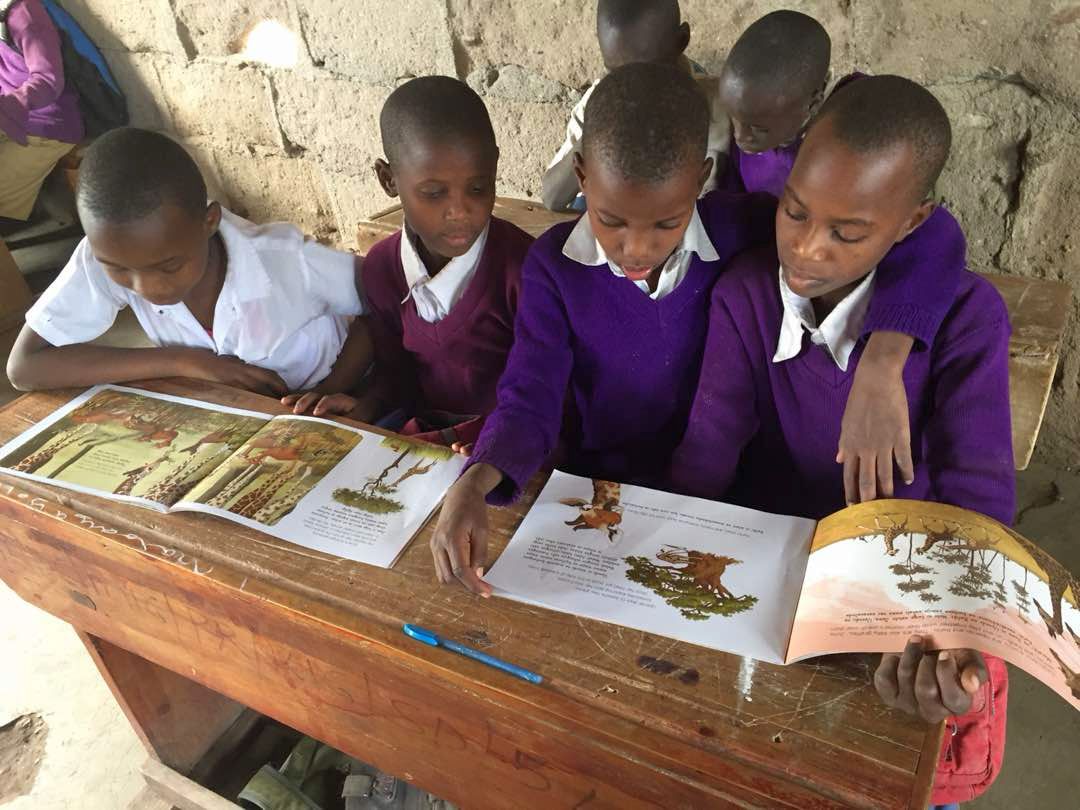

24 July 2018 Forest fires are not a serious threat to populations of Spotted Owls, contrary to current perceptions and forest management strategies. According to a new study, mixed-severity fires actually are good for Spotted Owl populations, producing more benefits than costs to the species, which acts as an indicator of biological health to the old-growth forests where they live. The study, which analyzed all 21 published scientific studies about the effects of wildfires on Spotted Owls, appears July 24 in the journal Ecosphere and suggests that management strategies for this species are outdated. “Current management strategies targeted at protecting Spotted Owls are prioritizing what is called fuel-reduction logging, which removes trees and other vegetation in a misguided and ineffectual attempt to reduce the severity of future fires,” said Derek E. Lee, associate research professor of biology at Penn State and author of the paper. “But this tactic removes canopy cover and large trees that are important for Spotted Owls and does not generally reduce fire severity of big, hot fires. The idea behind these logging projects is that the risks from wildfire outweigh the harm caused by additional logging, but here we show that forest fires are not a serious threat to owl populations and in most instances are even beneficial. This reveals an urgent need to re-evaluate our forest management strategies.” Spotted Owls are found in old-growth forests in the western United States and act as an indicator species, a measure of the biological health of an area, for public-land management. This species is particularly sensitive to logging, and when the northern subspecies of Spotted Owl was listed in 1990 as threatened -- likely to become endangered in the foreseeable future -- under the federal Endangered Species Act, about 90% of America’s old-growth forest had already been lost to unsustainable logging practices over the previous 50 years. The listing of the Northern and Mexican Spotted Owls as threatened drew national attention to the dramatic decline of old-growth forest ecosystems and forced policy changes in the management of national forests. In spite of these protections, populations of Spotted Owls have continued to decline outside of national forests over the last 38 years. Although many believe that wildfire has significantly contributed to this decline, there is little scientific basis for this assumption. “Much of what we knew about the Spotted Owl’s habitat preferences was derived from studies in areas that had not recently experienced fire,” said Lee. “I analyzed all available published studies investigating the effects of forest fires on Spotted Owls. I also considered the influence of fire severity. Forest fires in the western United States typically burn as mixed-severity fires that include substantial patches of low-, moderate-, and high-severity fire.” The new study shows that mixed-severity fires do not have any significantly negative effects on the owls’ choice of foraging habitat, survival, occupancy, reproduction, or recruitment. Although mixed-severity fires may lead to reduced occupancy -- the probability that certain sites are occupied by owls -- in burned areas, this reduction is less than is typically seen due to normal movement of the owls in unburned habitat, and is much less than what is observed in response to logging. Additionally, the risk of fire occurring in spotted owl breeding sites is very small: only 1 percent of breeding sites are affected by mixed-severity fires each year. Mixed-severity fires have a positive impact on the owls’ choice of foraging habitat, on the number of owls that are recruited to the area immediately after a fire, and on reproduction. High-severity fires, including those that burn 100 percent of an area, are also positively associated with reproduction. This indicates that even the most intense fires can have positive outcomes for Spotted Owls. “These positive effects indicate that the mixed-severity fires of recent decades, including so-called megafires that have been receiving lots of media attention lately, are within the natural range of variability for these forests,” said Lee. “The fact that Spotted Owls are adapted to these types of fires tells us that they have seen this before and learned to take advantage of it.” Together, these results suggest that, contrary to current perceptions, forest fires do not appear to be a serious threat to owl populations, and may impart more benefits than costs for Spotted Owls. Therefore, fuel-reduction logging treatments intended to mitigate fire severity in Spotted Owl habitat may in fact do more harm than good. “Spotted Owls were once a symbol of the biodiversity found in old-growth forests,” said Lee. “We need to reevaluate our management strategies to better protect these birds and the extraordinary biodiversity found in severely burned forests.” Contacts: Derek E. Lee: [email protected], (415) 763-0348 Gail McCormick: [email protected], (814) 863-0901 Wild Nature Institute teaches ecological and social lessons in Tanzanian schools with our Juma the Giraffe storybook. We focus on schools in communities adjacent to Tarangire and Lake Manyara National Parks, where we have been studying giraffes for 7 years. The goal is to inspire the next generation of Tanzanian giraffe conservationists.

|

Science News and Updates From the Field from Wild Nature Institute.

All Photos on This Blog are Available as Frame-worthy Prints to Thank Our Generous Donors.

Email Us for Details of this Offer. Archives

July 2024

|

|

Mailing Address:

Wild Nature Institute PO Box 44 Weaverville, NC 28787 Phone: +1 415 763 0348 Email: [email protected] |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed