|

California Spotted Owls are faring well in forests burned by the 2013 Rim Fire, the largest forest fire in recent history in the Sierra Nevada. A new paper in the scientific journal The Condor: Ornithological Applications documents nearly all (92%) of the historical Spotted Owl territories within the area burned by the Rim Fire were occupied in 2014, including sites where fire killed most of the large trees surrounding the owls’ nests and roosts. “The Rim Fire was particularly large and burned so many known territories that we had an excellent opportunity to see how the owls responded to this major disturbance event,” says Derek Lee of the non-profit research organization Wild Nature Institute and the study’s primary author. The U.S. Forest Service has assumed fire-killed forests are no longer Spotted Owl habitat and is currently logging the burned public forests, including occupied Spotted Owl territories, in spite of the decades of science showing logging, not fire, is the greatest threat to this quiet sentinel of forest ecosystems. In their study, the Institute’s scientists recommended that forest managers avoid logging burned Spotted Owls sites, even in large areas of fire-killed trees. Fire does not have the same negative impact on owls as logging, because owls have evolved over millennia with wildfire as a natural disturbance and can still find foraging habitat in burned areas if they are not logged. “Spotted Owls like lots of big old trees, whether those trees are alive or fire-killed, and they can find prey in shrubby areas regenerating after fire,” Lee notes. “Fire is not a threat to Spotted Owls, but logging is.” Forest fire leaves behind many dead standing trees for the owls to perch on and listen for their rodent prey. The rodents are likely eating the seeds and leaves of shrubs that are numerous in burned areas. Scientists call these heavily burned forests that have not been logged after fire “complex early seral” or “snag forests.” Such forests support a unique community of flora and fauna that depend upon the nutrient-rich post-fire conditions, including standing dead trees (snags), and fallen logs as habitat. Wild Nature Institute’s scientists analyzed field data forms and survey maps from U.S. Forest Service biologists, who searched for Spotted Owls one year after the Rim Fire at all 45 historical owl territories that were burned. They also investigated how the amount of high-severity fire surrounding owl locations affected occupancy probability. An average of 37%, and up to 100%, of the forested area around owl locations burned at high severity, yet no decrease in occupancy was evident for sites with Spotted Owl pairs, no matter how much burned at high severity. “Many people thought that the owls would have abandoned these sites in droves because the fire was so massive,” explains the study’s co-author Monica Bond. “Forest Service spokespeople had characterized the area as nuked, a moonscape, but then the agency’s own biologists detected owls at almost every territory.” The iconic California Spotted Owl is a species of conservation concern because it prefers older conifer forests for nesting, roosting, and foraging. The nocturnal bird of prey has long been at the center of debates over commercial logging on public lands, which impacted the owl’s forest habitat for more than a century and led to population declines. Some wildlife and forest managers point to forest fire as the most serious current threat to the species while ignoring logging—but recent studies have found California Spotted Owls usually remain in burned territories and forage on rodents in forests blackened by high-intensity fire. The Rim Fire study adds to the growing body of evidence that forest fire is not a major threat to Spotted Owls and actually produces many ecosystem benefits, including a unique pulse of biologically rich, complex young forests that are becoming increasingly threatened due to post-fire “salvage” logging.

0 Comments

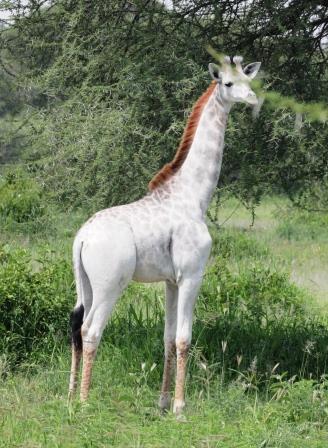

On our recent survey for giraffe in the Tarangire Ecosystem, we came across a stunning, nearly white giraffe calf. This giraffe was not albino, but leucistic. Leucism is when some or all pigment cells (that make color) fail to develop during differentiation, so part or all of the body surface lacks cells capable of making pigment. One way to tell the difference between albino and leucistic animals is that albino individuals lack melanin everywhere, including in the eyes, so the resulting eye color is red from the underlying blood vessels.

For the bird fans out there, enjoy some recent photos from Tarangire and Lake Manyara national parks. |

Science News and Updates From the Field from Wild Nature Institute.

All Photos on This Blog are Available as Frame-worthy Prints to Thank Our Generous Donors.

Email Us for Details of this Offer. Archives

July 2024

|

|

Mailing Address:

Wild Nature Institute PO Box 44 Weaverville, NC 28787 Phone: +1 415 763 0348 Email: [email protected] |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed