|

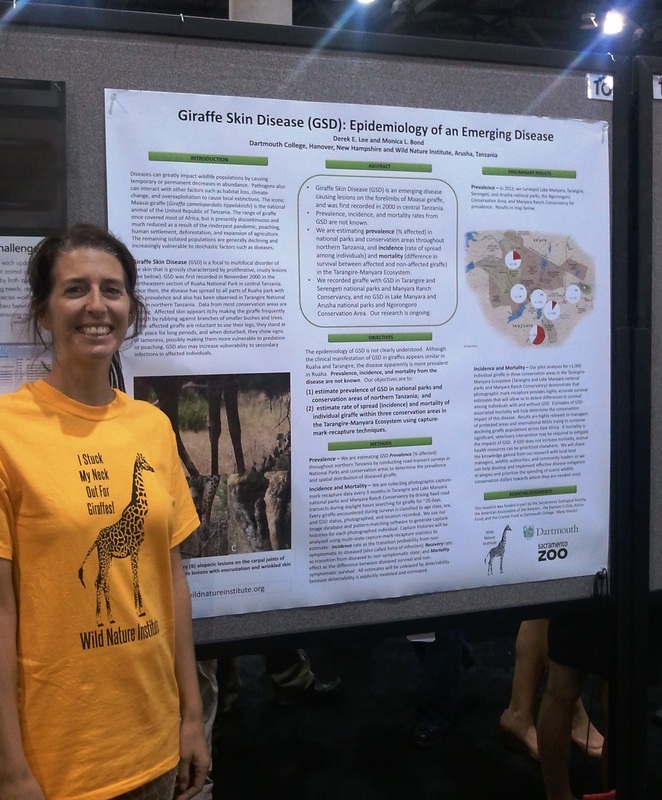

Giraffe Skin Disease (GSD) is a skin disorder that causes crusty lesions on the legs of Maasai giraffes. GSD was first recorded 12 years ago in Ruaha National Park in central Tanzania. Since then, the disease has spread to parts of northern Tanzania, including our study area. Affected skin appears itchy, making the giraffe frequently scratch by rubbing against branches of smaller bushes. Some affected giraffe are reluctant to use their legs; they stand at one place for long periods and show signs of lameness, possibly making them more vulnerable to predation or poaching. Very little is known about how many giraffes have this disease, and how it affects their survival. Wild Nature Institute scientists are estimating prevalence (% affected) in national parks and conservation areas throughout northern Tanzania, and incidence (rate of spread among individuals) and mortality (difference in survival between affected and non-affected giraffe) in the Tarangire-Manyara Ecosystem. We thank our supporters for helping us to study this emerging disease. We will share the knowledge gained from our research with local land managers, wildlife authorities, and community leaders so we can help develop and implement effective disease-mitigation strategies and prioritize the spending of scarce wildlife conservation dollars towards where they are needed most.

6 Comments

Anyone who has either traveled on safari in Africa or watched a nature show on television is probably familiar with one of the world’s most beautiful cats – the cheetah. This streamlined feline is perfectly adapted for speed, speed, speed. No other land mammal is as fast as the cheetah, which has a top speed of 60-70 miles per hour! But the adaption for speed comes with a price. As Richard Estes has noted in his excellent book, The Behavior Guide to African Mammals, “in acquiring the speed to catch the fleetest antelopes, the cheetah sacrificed the strength and weapons needed to defend its kills and offspring against competitors.” Lions, leopards, and wild dogs have all been known to kill cheetahs, and cheetahs also often lose their own kills to lions, wild dogs, and spotted hyenas.

We were very fortunate to see this mother and juvenile cheetah in Tarangire National Park during our dry-season ungulate surveys. A film crew from Tigress Productions visited our field site this week to interview Wild Nature Institute scientists Monica Bond and Derek Lee as part of a project on giraffe for the BBC and Smithsonian TV. We had a great time working with everyone involved and we'll let you know when the show is scheduled to air. Our dry-season survey yielded interesting results regarding detectability of certain ungulate species during different seasons. We noticed an increased ability to detect reedbucks, steenboks, and bushbucks. These antelopes are normally hidden in swamps (reedbucks), tall grasses (steenboks) or thick bushes (bushbucks). The lack of dense, tall vegetation allowed us to count substantially more of these animals than during any other season. Estimating detectability of each species in different vegetation types will allow us to accurately estimate their seasonal abundances. We provide this important information to Tanzanian wildlife authorities and national park staff as part of our long-term ungulate monitoring program.

An adult male giraffe, known as a bull, is the tallest animal on the planet, reaching a staggering 5.5 meters. Thanks to their great height, even widely dispersed giraffes can maintain visual contact with each other, and rival bull males react to one another from a long distance away. Younger males tend to associate in bachelor herds, but as they mature they become increasingly solitary. Bull males spend much of their time walking in search of females (cows) in estrus. A bull checks the reproductive status of a female by tasting her urine for particular hormones. When an estrous cow is encountered, the bull stays close to the female and attempts to keep rivals away. Bulls establish a dominance hierarchy based on seniority and the results of contests within bachelor herds. Click on the movie below to learn more about dueling between males, also known as “necking” or “sparring.”

During the dry season, most of the migratory animals like zebras, wildebeests, elands, and buffalo in the Tarangire-Manyara Ecosystem are congregated in Tarangire National Park because the river and nearby waterholes are the only reliable and abundant source of drinking water in the region. Not surprisingly, these dense congregations of ungulates provide a bonanza of food for the park's population of African lions. The ungulates are well aware of the perils of being forced to congregate in a limited area, but they have no choice - they simply have to drink water to survive. They are always on the lookout for the hidden, lurking danger at the waterhole.

|

Science News and Updates From the Field from Wild Nature Institute.

All Photos on This Blog are Available as Frame-worthy Prints to Thank Our Generous Donors.

Email Us for Details of this Offer. Archives

July 2024

|

|

Mailing Address:

Wild Nature Institute PO Box 44 Weaverville, NC 28787 Phone: +1 415 763 0348 Email: [email protected] |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed