|

World Giraffe Week 2024 in Tanzania was a resounding success, thanks to our fantastic education coordinator Veila Makundi and our entire Wild Nature Institute team. We welcomed our newest member of the education team, Glory Mbuya, and James Madeli helped out and took lots of great photos and videos of the activities. The kick-off to World Giraffe Week was interviews by Wild Nature Institute's Veila Makundi on 2 Arusha-based radio stations reaching thousands of Tanzanias about giraffes and what everyone can do to protect them. Then it was off to the schools for activities! More than 540 kids and teachers from 5 schools participated, with a highlight being a 'ngongoti', a man on stilts dressed like a giraffe, which delighted the children. The children made giraffe posters with unique spots (to be delivered to park rangers on World Ranger Day, 31 July), danced and sang, and had a great time celebrating Tanzania's national animal and learning how they can help save them. Of course, absolutely none of this would have been possible without the amazing support from our donors around the world. Thank you so very much, from all of us at Wild Nature Institute.

0 Comments

This year's theme is GIRAFFE SPOTS! Visit www.worldgiraffeweek.org to learn more about their spots and to try some fun activities to celebrate our tall friends!

Food, then sex, drove the evolution of the giraffe's long neck, according to a new study by Penn State and Wild Nature Institute published in the journal Mammalian Biology. Although male and female giraffes have the same body proportions at birth, they are significantly different as they reach sexual maturity. Females have proportionally longer necks and longer bodies than males, which might help with foraging and child rearing, while males have wider necks and longer front legs, which might help win fights against other males and with mating. Credit: Penn StateWhy do giraffes have such long necks? A study led by Penn State biologists explores how this trait might have evolved and lends new insight into this iconic question. The reigning hypothesis is that competition among males influenced neck length, but the research team found that female giraffes have proportionally longer necks than males—suggesting that high nutritional needs of females may have driven the evolution of this trait.

The study, which explored body proportions of both wild and captive giraffes, is described in a paper that appeared today, June 3, in the journal Mammalian Biology. The findings, the team said, indicate that neck length may be the result of females foraging deeply into trees for otherwise difficult-to-reach leaves. In their classic theories of evolution, both Jean Baptiste Lamarck and Charles Darwin suggested that giraffes' long necks evolved to help them reach leaves high up in a tree, avoiding competition with other herbivores. However, a more recent hypothesis called "necks-for-sex" suggests that the evolution of long necks was driven by competition among males, who swing their necks into each other to assert dominance, called neck sparring. That is, males with longer necks might have been more successful in the competition, leading to reproducing and passing their genes to offspring. "The necks-for-sex hypothesis predicted that males would have longer necks than females," said Doug Cavener, Dorothy Foehr Huck and J. Lloyd Huck Distinguished Chair in Evolutionary Genetics and professor of biology at Penn State and lead author of the study. "And technically they do have longer necks, but everything about males is longer; they are 30% to 40% bigger than females. In this study, we analyzed photos of hundreds of wild and captive Masai giraffes to investigate the relative body proportions of each species and how they might change as giraffes grow and mature." The researchers gathered thousands of photos of captive Masai giraffes from the publicly accessible photo repositories Flickr and SmugMug as well as photos of wild adult animals that they have taken over the past decade. Because absolute measurements like overall height are difficult to determine from a photograph without a point of reference of known length, the researchers instead focused on measurements relative to one another, or body proportions—for example, the length of the neck relative to the entire height of the animal. They restricted their analysis to images that met strict criteria, such as only using images of giraffes perpendicular to the camera, so they could consistently take a variety of measurements. "We can identify individual giraffes by their unique spot pattern," Cavener said. "Thanks to the Association of Zoos and Aquariums, we also have the full pedigree, or family tree, of all Masai giraffes in North America in zoos and wildlife parks, as well as their birthdates and transfer history. "So, by carefully considering this information, when the photo was taken and the approximate age of the animal, we could identify the specific individual in nearly every photo of a captive giraffe. This information was critical to understanding when male and female giraffes start to exhibit size differences and whether they grow differently." Giraffe body proportion measurement landmarks and definitions. Measurements are performed on images that are perpendicular to the plane of the body trunk and neck. Measurements were performed between landmarks lying along the two-dimensional perimeter of the giraffe. Credit: Mammalian Biology (2024). DOI: 10.1007/s42991-024-00424-4At birth, male and female giraffes have the same body proportions. The researchers found that, although males generally grow faster in the first year, body proportions are not significantly different until they start to research sexual maturity around three years of age. Because body proportions change early in life, the team limited their study of wild animals—whose ages are largely unknown—to fully grown adults. In adult giraffes, the researchers found that females have proportionally longer necks and trunks—or the main section of their body, which does not include legs or the neck and head. Adult males, on the other hand, have longer forelegs and wider necks. This pattern was the same in both captive and wild giraffes. "Rather than stretching out to eat leaves on the tallest branches, you often see giraffes—especially females—reaching deep into the trees," Cavener said. "Giraffes are picky eaters—they eat the leaves of only a few tree species, and longer necks allow them to reach deeper into the trees to get the leaves no one else can. Once females reach four or five years of age, they are almost always pregnant and lactating, so we think the increased nutritional demands of females drove the evolution of giraffes' long necks." The researchers noted that sexual selection—either competition among males or preference among females for larger mates—was likely responsible for the overall size difference between males and females, as is the case in many other large, hoofed mammals that are polygynous—where one male mates with many females. They suggest that, following the evolution of the long neck, sexual selection—including male body pushing and neck sparring behaviors—may have contributed to males' wider necks. Additionally, the longer forelegs of males may assist in mating, which the researchers said is a brief and challenging affair that is rarely observed. "Interestingly, giraffes are one of few animals whose height we measure to the top of the head—like humans—rather than to their withers—the highest part of the back, like in horses and other livestock," Cavener said. "The female has a proportionally longer axial skeleton—a longer neck and trunk—and are more sloped in appearance, while the males are more vertical." The research team is also using genetics to identify relationships in groups of wild giraffes to better understand which males are successful at breeding. The goal is to shed additional light on mate choice and sexual selection, as well as guide conservation efforts for this endangered species. "If female foraging is driving this iconic trait as we suspect, it really highlights the importance of conserving their dwindling habitat," Cavener said. "Populations of Masai giraffes have declined rapidly in the last 30 years, in part due to habitat loss and poaching, and it is critical that we understand the key aspects of their ecology and genetics in order to devise the most efficacious conservation strategies to save these majestic animals." In addition to Cavener, the research team at Penn State includes Monica Bond, academic affiliate of biology; Lan Wu-Cavener, academic affiliate of biology; George Lohay, a postdoctoral researcher at the time of the research who is now at the Grumeti Fund; Mia Cavener, a graduate student at the time of the research; Xiaoyi Hou, graduate student in the Molecular, Cellular, and Integrative Biosciences program; David Pearce, an undergraduate student at the time of the research; and Derek Lee, academic affiliate of biology. Funding from Penn State, the Penn State Huck Institutes of the Life Sciences and the Wild Nature Institute supported this research. Wild Nature Institute’s CAG education program organized a two-week Snake Blitz to teach Tanzanian children and teachers appreciation for snakes and prevent snake bites—which saves people and snakes alike. From 19 February to 3 March, a whopping 1,694 children from 5 primary schools in the Monduli district participated in the event, and learned all about the ecological importance of snakes, snake identification, how to behave around snakes to avoid conflict, and what to do if bitten. The kids learned through fun activities such as dramatic demonstrations and memory games, as well as with a beautiful snake activity book designed by our collaborators Mirthe Aarts and Megan Strauss together with Monica Bond, and produced by WNI. Children were given a questionnaire to fill out before and after participating, so we can quantify what the children learned and how our Saving People Saving Snakes education program affected their perceptions about snakes.

We warmly welcomed Gwido Aldo to our Saving People Saving Snakes program (see attached photos). Aldo is a Tanzanian snake expert and works with Tanzania Snake Conservation Education and Awareness (TASCEA) developing and delivering snake educational and awareness programs and collaborating with authorities to protect critical snake habitats. He is the perfect person to join our education team to share with children the importance of respecting these misunderstood and maligned reptiles. Veila and Jackline did an absolutely amazing job organizing the Snake Blitz with 2 visits to each of the 5 primary schools. They distributed 700 snake activity books, brought 175 children to visit the Meserani Snake Park to see snakes first-hand, and took 62 kids on a nature walk near the school. It was an exhausting but productive two weeks! As always, we are deeply grateful to our donors for funding our CAG education program. While this activity was not directly about giraffes, our Saving People Saving Snakes project fosters respect and appreciation for all species in nature which bolsters community support for protecting all wildlife, including giraffes. New research shows that for antelope populations in East Africa, it is not just about the weather but where they can roam. This highlights why we need big, connected spaces for conservation. Environmental changes threaten naturally heterogeneous and dynamic ecosystems that are essential in creating and maintaining a rich, resilient, and adaptable biosphere. In East Africa’s savanna, antelope populations are vital for a healthy and functioning ecosystem. They shape the vegetation, disperse seeds, cycle nutrients, and provide food for other animals. A natural dynamic mosaic of vegetation types, water sources, and weather forms a delicate balance with the antelopes that is more and more disrupted by human influences and climatic changes. To protect these hotspots of biodiversity and enable the ecosystem to work properly, it is vital to maintain healthy antelope populations. Previous studies have shown that densities of savanna antelopes vary based on location, season, and year, but no empirical studies had ever examined all these effects together. Simultaneously studying how environmental variation over space and time affects the local densities of antelope species could resolve whether location, or seasonal or annual variation is the most important factor driving local densities of these wildlife. Using seven years of antelope monitoring data from the Tarangire Ecosystem in Tanzania, an international collaboration between the University of Zurich and the Wild Nature Institute examined this question. They found spatial factors explained the largest proportion of variation in density for four of the five antelope species they studied. These spatial covariates included proximity to water and human activities as well as vegetation community—suggestive of both bottom-up (resources) and top-down influences (avoiding natural predators) on local densities. The research was published in the journal Population Ecology. In the Tarangire Ecosystem, antelopes respond to changing climatic conditions and the fluctuating availability of resources by moving across space. Lead author Lukas Bierhoff, a graduate student in the Department of Evolutionary Biology and Environmental Studies at University of Zurich, said “these results demonstrate that antelopes depend upon water and forage availability, but are flexible in their responses to climatic variation when they have the option to move and seek out the necessary resources for the current conditions.” Helping antelopes move across space to adapt to climate and habitat changes As natural savanna habitats and climate are rapidly being altered by human activities, effective conservation strategies are needed to ensure the persistence of antelopes and all the services they provide to maintain healthy ecosystems. “This study provides further evidence that the protection of large, connected areas of different habitat types and permanent water sources are the best way to maintain high biodiversity and a functioning biosphere. Providing habitat options for the antelopes enables them to respond to a temporally changing world by moving across space,” Bierhoff said. The research team also identified guilds of antelopes whose densities co-varied, and that might respond similarly to targeted and coordinated conservation strategies, thus increasing the efficiency of management actions. “Effective conservation actions include protecting rivers and other water sources from diversion and pollution; reducing bushmeat poaching; keeping and restoring movement corridors; and maintaining the diversity of natural vegetation types” said Derek Lee, Wild Nature Institute principal scientist and senior author of the paper. “Antelopes are critically important to Tanzania’s economy as well as its ecology, so sustaining thriving populations of these animals is a win-win for people and wildlife.” Citation: Bierhoff L, Bond, ML, Ozgul A, Lee DE. 2024. Anthropogenic and climatic drivers of population densities in an African savanna ungulate community. Population Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1002/1438-390X.12182

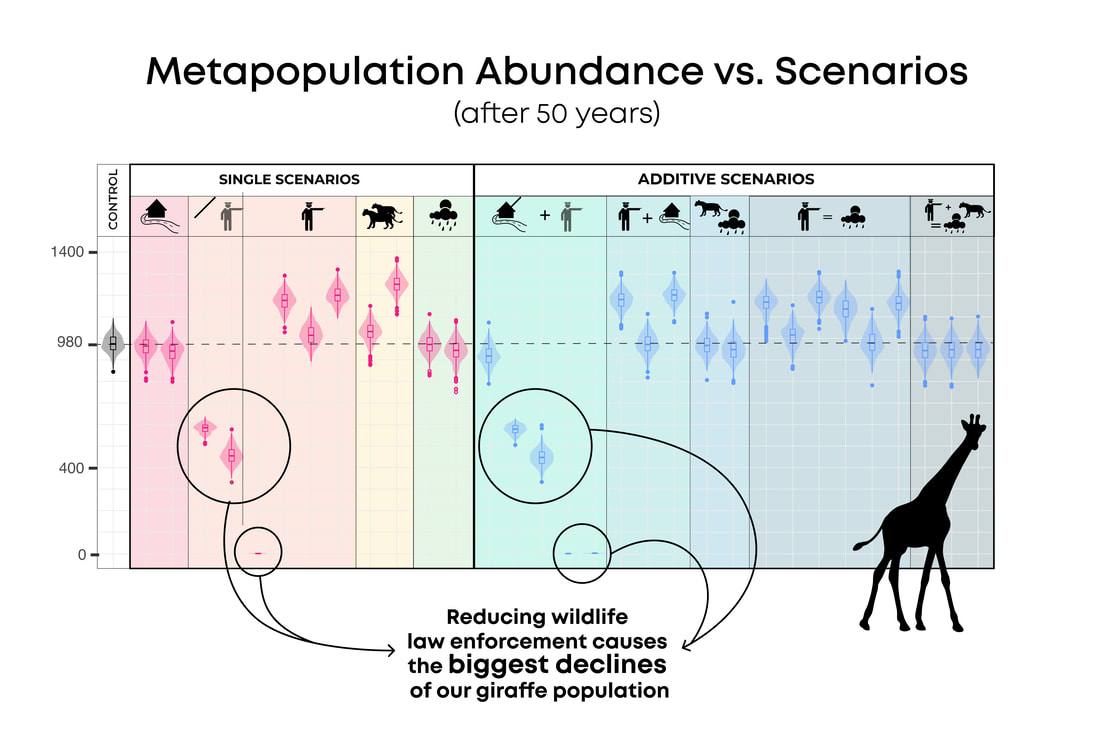

In 2023, the Wild Nature Institute continued our Science, Education, and Advocacy for wildlife in savannas of East Africa, a biologically rich region threatened by human activities.

We completed another year of the world’s largest study of giraffes using non-invasive photographic identification and DNA sampling. Together with our research partners around the world we published 4 new scientific papers about giraffes, and shared our results with other scientists, students, government decision-makers, and the media. Our Celebrating Africa’s Giants education program reached ever more communities in Tanzania. Children learned about wildlife, ecology, and conservation in their classrooms; celebrated World Giraffe Week and Elephant Fun Day; nurtured and planted trees; and visited their local national parks for the first time. Click here to learn about our accomplishments in 2023. We could not have met our goals without the support of our donors and partners. We are deeply grateful, as always. More than 2000 schoolchildren and teachers from 6 schools in the Mtowambu area of Tanzania celebrated Elephant Fun Day on 27 October, hosted by Wild Nature Institute! The day kicked off with a big parade through town with costumes, banners, and posters, and culminated with a football and netball sports tournament for girls and boys! We also provided a healthy lunch for all participants. Thank you to all of our partners and donors for helping us show the community that we love elephants and want to protect them! Iconic animals such as giraffes can be flagship species for conservation because of their charisma and popularity among the public. A new study explored the various threats to giraffe populations, and how specific human actions can mediate those threats so that giraffes and people can thrive together in African savannas. The giraffe is an icon of the African savannas, instantly recognizable with its unique shape and height and dazzling spot patterns. Yet despite the popularity of giraffes around the world, they face major challenges to their continued surviving in the wild. Numbers of giraffes and other large, charismatic animals such as elephants and rhinos have plummeted, and giraffes are now listed as an endangered species. In research published today in the journal Global Change Biology, scientists from the Doñana Biological Station, Penn State University, and Wild Nature Institute showed that effective wildlife law enforcement which protects giraffes from illegal hunting is the best way to keep giraffe populations healthy and thriving.  Giraffes are physically large, so they require a lot of space to move around. They live a long time, nearly 30 years, and are slow to breed, with giraffe mothers first giving birth at the age of 6 and producing only one calf about every 2 years thereafter. Giraffes are increasingly in danger from one of the most cunning predators of all: people. Giraffes are killed by poachers working for criminal syndicates to sell their meat and body parts in bushmeat markets. Giraffes are also losing their natural savanna habitat to farms and urban sprawl, and climate change is increasing heavy rainfall events which spread diseases that cause giraffe deaths. To conserve giraffes we need to know which natural- and human-caused pressures are most important in driving their population declines, and whether human actions could mediate the threats. In this study the scientists aimed to understand how changes in land use, illegal hunting, and rainfall affected the abundance of Masai giraffes in the human-impacted Tarangire region of Tanzania in East Africa. This region hosts two world-class national parks, an ecotourism livestock ranch, and village lands, all with different levels of land and wildlife conservation. The scientists have monitored giraffes in the area for nearly a decade to learn how each of these threats influences giraffe survival. The researchers then combined the information they learned from previous studies to create an individual-based model that simulated realistic population dynamics and extinction risk under different scenarios of environmental change over 50 years. They tested a set of credible threats to the persistence of giraffes in this system, including an expansion of towns along the edges of the study area, loss of connectivity between key habitat areas, improved or reduced wildlife law enforcement, changes in predation pressure on giraffe calves from changes in lion and wildebeest populations, and more heavy rainfall events as predicted for East African savannas. They also tested combinations of scenarios, as well as management actions that could mitigate the threats. The study showed that the greatest risk of population declines and extinction for giraffes is caused by a reduction in wildlife law enforcement leading to more poaching. Furthermore, an increase in law enforcement would mitigate the effects of the most extreme predicted increases in heavy rainfall and the expansion of towns. The study highlights the great utility of law enforcement as a nature conservation tool. The scientists’ research demonstrated that giraffes benefit from the presence of traditional livestock herders on the rangelands outside parks that are shared by giraffes and pastoralists. The problems arise when giraffe rangeland habitat is plowed into farms, when towns and other development sprawl into the habitat and force giraffes to move longer distances to find food and water, and when people kill giraffes for bushmeat markets. The scientists recommend that wildlife law enforcement be expanded in village lands outside of protected areas, legal livelihoods be promoted to reduce the perceived need for poaching for income, and wildlife movement pathways be permanently protected from farming, mining, and infrastructure to enable giraffes and migratory wildebeest to access high-quality habitats. These measures would increase the population of giraffes in the Tarangire region and contribute to the recovery of this endangered species, while ensuring people and giraffes thrive together. Citation: Bond ML, Lee DE, Paniw M. Extinction risks and mitigation for a megaherbivore, the giraffe, in a human-influenced landscape under climate change. Global Change Biology. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/gcb.16970 We are excited that 5 members of the Wild Nature Institute giraffe research and education team attended the International Congress on Conservation Biology in Kigali, Rwanda at the end of July. We presented 4 talks about our giraffe research to an international audience of conservation biologists and educators:

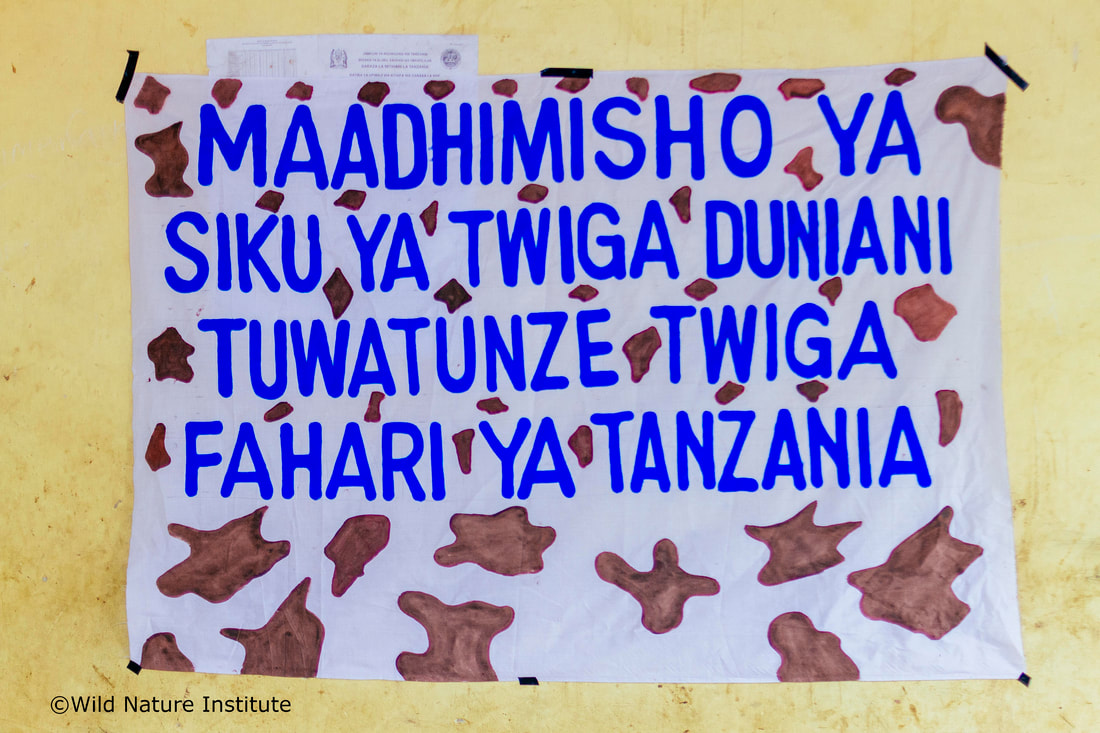

The Wild Nature Institute honored World Giraffe Day 2023 on 21 June with a celebration involving primary school students and Maasai women groups living in the Tarangire-Manyara Ecosystem, one of the most important ecosystems for giraffes in Tanzania. The aim was to share with the community that the giraffe population is declining. We used arts and crafts, songs and dances, and talks from experts about giraffes to share this message. The students drew pictures of giraffes, and the Maasai women designed giraffe-themed handicrafts, and other items such as pots, cups, and plates that were spotted like giraffe spots using clay soil. Some women used beads to make bracelets, earrings, and necklaces that represented giraffes. James Madeli, Wild Nature Institute’s Tanzanian research coordinator, spoke with the community members about how giraffes are surviving in the wild. He noted that the giraffe population is declining due to loss of habitat, poaching, and climate change effects. The Maasai play a big role in conservation by protecting rangelands for their livestock, thus benefiting wild animals too. Every group presented what they had created, and sang traditional songs for giraffe day. This was an exciting part of the event because everyone was happily showing off and making fun drama and competing to be the best group. We also handed out World Giraffe Day t-shirts to participants. The event closed with soft drinks and delicious food that was cooked by the villagers themselves. The groups sent words of gratitude to the Wild Nature Institute and all our partners in conservation who helped make this event possible. It was indeed an educational—but most importantly FUN—week, from the schools to the community. More than 200 women, men, and children were reached on World Giraffe Day.

|

Science News and Updates From the Field from Wild Nature Institute.

All Photos on This Blog are Available as Frame-worthy Prints to Thank Our Generous Donors.

Email Us for Details of this Offer. Archives

July 2024

|

|

Mailing Address:

Wild Nature Institute PO Box 44 Weaverville, NC 28787 Phone: +1 415 763 0348 Email: [email protected] |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed